View the PDF here

The Invisible U.S. Fire Problem

By: Brian Meacham, Meacham Associates, USA; Sandra Vaiciulyte, Kindling, Mexico; Danielle Antonellis, Kindling, USA; Charles Jennings, John Jay College of Criminal Justice / CUNY, USA

This article is excerpted with modification from the published report, Antonellis, D., Vaiciulyte, C., Meacham, B.J. and Jennings, C. (2022). The Invisible U.S. Fire Problem, Kindling Inc. and the National Fire Protection Association, https://www.nfpa.org/-/media/Files/News-and-Research/Fire-statistics-and-reports/US-Fire-Problem/osInvisibleUSFireProblem.pdf, reprinted with permission.

Framing the Problem

The primary narrative about safety to life from fire in the United States (US) is a success story. With the introduction of smoke alarms, social changes such as a reduction in smoking, improvements in building, fire and electrical codes and standards, introduction of other forms of safety protection technologies, and improved emergency response and healthcare for much of the population, fire deaths have reduced dramatically since 1980. But this is not the whole story.

In the US, the demand for affordable housing often outstrips supply. There are also social equity challenges that impact access to funding mechanisms. In response to such socioeconomic and social equity issues, people are often forced to find or create alternative living arrangements. Unfortunately, some of the shelters that people are forced to use fall outside the purview of state legal systems of land ownership and tenure, and of planning, land use, building, public health and safety regulations. These shelters can be considered under-regulated or unregulated. Some people are forced to go unsheltered.

The US housing problem contributes to hundreds of thousands of people being homeless and millions of people living in undesirable conditions due to inadequate shelter conditions: overall, millions of insecurely housed people. Many of these insecurely housed people are at higher risk to life from fire, due both to the shelter vulnerabilities and human vulnerabilities to fire. However, the risk to life from fire of insecurely housed people is generally undocumented and the scope of the problem is largely unknown. Significant research is needed, but where to start?

Figure 1. Graphical illustration of intersection of shelter vulnerabilities and human vulnerabilities to fire [1].

Reframing this issue through a regulatory lens can offer new perspectives. What do we know about under- and unregulated buildings? What do we know about fire in under- and unregulated construction? What fire challenges do occupants of under- and unregulated structures – people who are homeless or insecurely housed – face given the confluence of shelter and human vulnerability to fire? What is the scope of this ‘invisible’ fire problem?

The answers to these questions are critically important. Understanding the nature of insecurely and vulnerably sheltered persons is important for several reasons, most notably the ability to identify measures to improve fire safety across the range of existing shelter and housing in the US, and the need to situate these measures in the context of the complex US building regulatory system, so that fire risks, and risks to safety from fire in these shelters, can begin to be addressed.

Shelter Typologies & Fire Vulnerabilities

For the purposes of our work, shelter is considered from the perspective of five broad categories:

- Vulnerability-Protected: Goes beyond minimum aspect of building code and includes additional provisions / enhancements aimed at protecting shelters and their vulnerable populations more robustly from fire than minimally compliant shelters.

- Minimally Compliant: Meets building code requirements at time of construction and are maintained to meet that level throughout their lifetime to provide a societally tolerated level of shelter vulnerability to fire.

- Under-Regulated: May have met building code at time of construction, or not, and are inadequately maintained, have insufficient fire protection, may have illegal components, may be abandoned, etc. Also, persons may use the space for temporary or permanent shelter, legally or illegally. Occupants may use open flame cooking and heating. Examples include:

- Under-Maintained: The situation of a once compliant building falling into neglect due to an owner unwilling or unable to address maintenance issues. This can occur with owner occupied or rented housing. These buildings are typically considered occupied, even if the level of habitability is poor (see also abandoned or vacant buildings).

- Under the Radar: These are buildings which have not gone through any formal building regulatory process as part of alterations or repurposing. Significant concerns include illegal construction, illegal conversion or subdivision of space, and insecure tenure for occupants. Also, the fire service may be unaware of occupant numbers.

- Vacant / abandoned: The buildings are not formally occupied and may be in significant states of disrepair or damage. Many of these buildings lack any type of fire protection measures, do not have active utilities connections (e.g., power, water), and may be filled in part with discarded belongings, trash, or other combustibles. If people are using such buildings for shelter, they may be using open flame for cooking and heating, presenting significant fire ignition hazards. Likely the fire service will not know the building has occupants should a fire occur.

- Unregulated: Informal structure built outside of regulatory control or other means of shelter. Informal construction may use temporary materials and methods of construction to provide minimal protection from the environment. The construction likely offers little or no fire protection. Insecure tenure is common. Examples include shacks, lean-to’s, tents, tarps, lean-to’s, motor vehicles. Occupants may use open flame cooking and heating.

- Non-sheltered: No significant form of shelter. Open sleeping, possibly with bedding or other cover (e.g., bridge, doorway, awning, cardboard) for minimal protection against weather conditions. This is the highest level of shelter insecurity and vulnerability. Maybe located adjacent to open flame heat sources.

Human Vulnerabilities & Fire

Human vulnerability to fire results from many individual and social factors, in addition to any factor associated with shelter construction. Factors that make humans vulnerable to fire have been studied by many. In our review, we found that some of the suggested predictors are ambiguous or contradictory across the geographically diverse studies. This makes it difficult understand specifically the contribution to risk to life from fire. Furthermore, some of the vulnerability factors can be contextual, which makes it challenging to consider in a comparative manner.

However, from the reviewed literature, we identified 18 broad categories that indicate human social, demographic and economic vulnerability that contributes to risk to life from fire. Generally, individual habits (e.g., use of alcohol drugs, smoking), physical psychological fitness (e.g., mental or physical health conditions), demographics (age and gender, family structure), economic status (identified as either poverty, household income, employment status, or education), and social belonging, often explored on the basis of individual background (e.g., ability to speak local language, ethnicity, inclusion in community) were the recurring predictors of general fire risks.

It is evident from the literature that household income, poverty and family structure have been shown to translate to poor dwelling conditions with most certainty. However, it is also evident that many of the sociodemographic factors are not being explored beyond the ‘general risks of fire’. For example, it has been largely unexplored in the sample of the reviewed literature, whether ethnicity, ability to speak the local language, employment status, gender, smoking and use of intoxicating substances bear relationship to any dwelling characteristics. These factors, however, all were shown to matter for general fire risks. Thus, the lack of evidence for specific sociodemographic factors and their relationship to dwelling characteristics limits our ability to understand diversity of insecurely and vulnerably sheltered populations in terms of age, gender, inclusion in community and their income, and how this diversity interacts with fire risk.

Risk to Life from Fire in Different Shelter Typologies

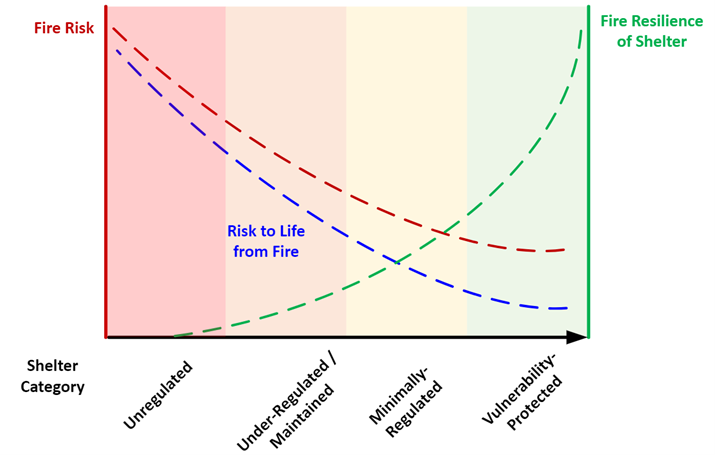

The invisible fire risk is a complex problem which has just started to be explored. From a purely qualitative, graphical perspective, review to data suggests a relationship between the fire vulnerability of a shelter and the risk to life from fire of the occupants. This is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Graphical illustration of risk to life from fire by shelter typology [1].

The red line reflects risk of fire occurring (fire risk) for the different typologies. The green line reflects the inverse – the fire resilience of the typologies. The blue line indicates risk to life from fire, which decreases from left to right indicating unregulated shelters present higher levels of risk to life from fire than the other shelter categories. There is a strong relationship between risk to life from fire and fire risk - they are interrelated. Regulatory mechanisms that prioritize life safety drive fire safety investments therefore reducing fire risk overall. Vulnerability-protected shelters go beyond regulatory requirements and include features that provide additional protection for one or more vulnerability attributes (e.g., could be enhanced fire protection features, enhanced evacuation features, care givers, etc.). under- and unregulated shelters have little or no fire protection, high fire risk, and significant risk to life from fire. This may seem obvious but has not been well studied. Data are lacking. Much needs to be done.

The Invisible Fire Problem Knowledge Iceberg

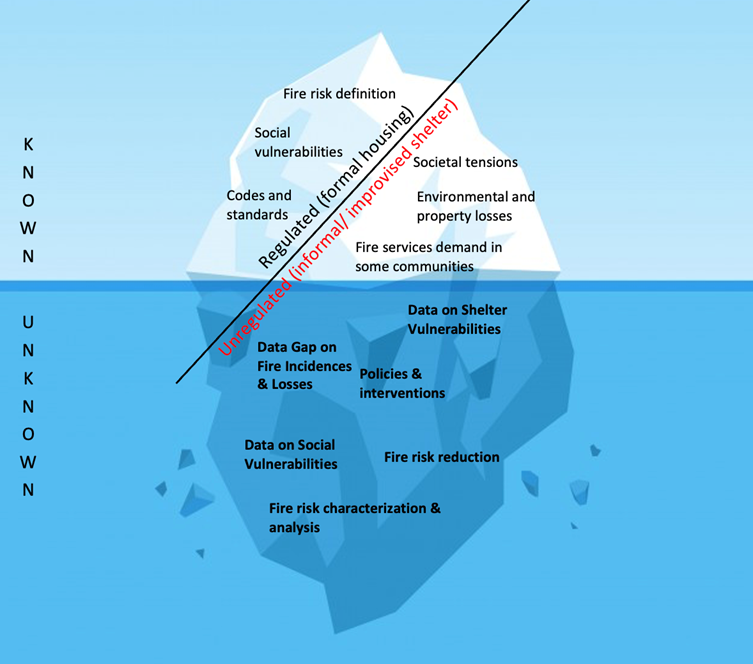

Our initial work has identified gaps in research, policy, and action pertaining to fire safety of insecurely and vulnerably sheltered populations in the US. It suggests that fire disproportionately affects populations in under-regulated, unregulated, and non-sheltered living conditions, despite significant challenges quantifying and describing fire risks and consequences on a national level – hence it is termed here the invisible US fire problem. Playing off this imagery of invisibility, an illustration of an iceberg is used to describe known and unknown dimensions of these fire problems (Figure 3).

The tip of the iceberg represents the known areas of fire safety in regulated housing and in unregulated shelter that are commonly engaged with in research, policy making and are present in the news media and activism. These are the ‘known’ areas that support our thinking about fire safety currently. The illustration of the iceberg extends under-the-water, to the ’known unknowns’, to illustrate research, policy making and activism gaps in relation to what is currently known about fire safety in insecure and vulnerable shelters. Currently, no consolidated effort exists to tackle these issues in an integrated, transdisciplinary way, where multiple research objectives converge. The water represents ‘unknown unknowns’, factors that may affect fire safety in these settings, but have not yet been identified.

Figure 3. Research gaps specifically for vulnerably sheltered [1].

As shown in Figure 3, several gaps and challenges exist, including:

- Lack of data on shelter vulnerabilities

- Lack of data in fire incidence concerning homeless populations

- Insufficient policies and interventions that address under-regulated, unregulated, and non-sheltered typologies

- Lack of strategies for fire risk reduction

- Lack of data on social vulnerabilities of vulnerably and insecurely housed populations

- Lack of fire risk characterization and analysis methods

Where to from Here?

To tackle holistically and urgently the identified gaps and improve fire safety across insecurely and vulnerably shelter contexts, stakeholders need to collaboratively engage with this ‘invisible’ fire safety problem through research, policy and action that addresses the full spectrum of economic, social, and technical issues. The roles of public health data services, social services engaging with homeless populations, firefighters, fire engineers and academics among others are significant. Convergent transdisciplinary action research is needed. The needs and actions identified in this section should be viewed as a starting point, and not an exhaustive list. It is important to engage with multiple stakeholders to address challenging and emerging fire safety gaps in these settings. In the USA, it is suggested that workshops should be held with relevant stakeholders, such as NFPA, DHS/USFA, HUD, code enforcement entities, the Urban Institute, Vacant Property Research Network, Center for Community Progress, Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, to develop more specific strategies and to identify funding opportunities for research and action. While not explicitly addressed in this work, it is suggested that the ‘invisible’ fire safety problem exists in many other countries, and that the approach of convening stakeholder workshops, undertaking research strategy development, and exploring funding opportunities to support research and policy development within this space would be worthwhile in many other countries and regions of the world as well.

References

[1] Antonellis, D., Vaiciulyte, S., Meacham, B.J. and Jennings, C. (2022). The Invisible U.S. Fire Problem, Kindling Inc. and the National Fire Protection Association, https://www.nfpa.org/-/media/Files/News-and-Research/Fire-statistics-and-reports/US-Fire-Problem/osInvisibleUSFireProblem.pdf