View the PDF here

Wildfires at the Wildland-Urban Interface in Mexico: An Emerging Risk

By: Sandra Vaiciulyte, Institute of Geophysics, National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico; Alejandro Rivero-Villar, Instituto de Estudios Superiores de la Ciudad de México “Rosario Castellanos”, Mexico; Louise Guibrunet, Institute of Geography, National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico.

This is an abridged version of the following publication: Vaiciulyte, S., Rivero-Villar, A. & Guibrunet, L. Emerging Risks of Wildfires at the Wildland-Urban Interface in Mexico. Fire Technol 59, 983–1006 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10694-023-01376-w

Urbanisation and climate change are thought to be the two biggest challenges the population across the globe faces in the 21st century, and a trans-national community of scientists and governments have recently emphasised the adverse effects to humans brought about by these challenges [1;2;3].One of their concerns is the increased risk of wildfires and its impacts on humans.

Fires, and more specifically wildfires at the wildland-urban interface / intermix (WUI) are among the hazards that develop into ecological and human disasters [4] and that manifest whenever wildfire season occurs. WUI wildfires and related disasters have been most commonly researched in the USA, Canada, Australia, and Southern Europe [5;6;7;8], although more diverse geographies have begun to gain scholarly interest, such as Sweden, the United Kingdom, and Argentina [9;10;11;12].However, despite projections of increased wildfire risk in the future in diverse regions of the world [13;14], which will be exacerbated by fragmented patterns of urbanisation (which expands the WUI) [15;16], research on wildfire risk in diverse geographies remain scarce.

The Mexican territory has some geographical and social characteristics that suggest wildfire risk: those include dry weather, high fuel loads across the landscape, territory-wide presence of wildfires, a largely urbanised population and an expected growth of small and mid-sized cities, mostly through periurban expansion [17;18;19]. Wildfire research using modelling and projections is identifying a worsening trend [20;21]. Yet, WUI fires do not promptly come to mind when one thinks of hazards affecting the Mexican population. The country is routinely affected by other hazards such as hurricanes, floods, landslides, tornadoes and earthquakes, which also affect populations. Instead, wildfire tends to be portrayed in the Mexican literature as a threat to forest ecosystems produced by human-environmental interactions (see, for instance: [22;23;24]). That is to say, populations at the WUI tend to be seen as the cause of fire rather than as exposed to a hazard. Although these perceptions are slowly evolving, no mention of the effects of fires on WUI communities exists in the literature.

This paper sets out to understand if WUI wildfires exist in Mexico and if they present risk to populations. We show a pattern of emerging WUI wildfire risks and conclude that substantial attention should be paid to mitigation, adaptation and recovery from such fires in WUI communities in Mexico.

Research questions

Research question 1: Are there actually wildfires at the WUI in Mexico?

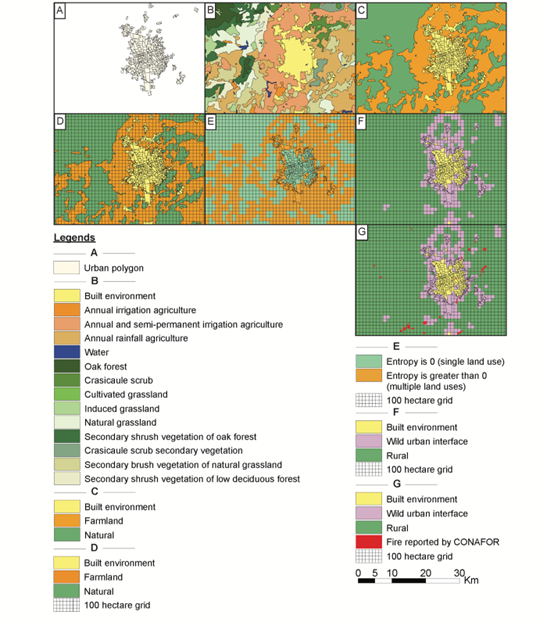

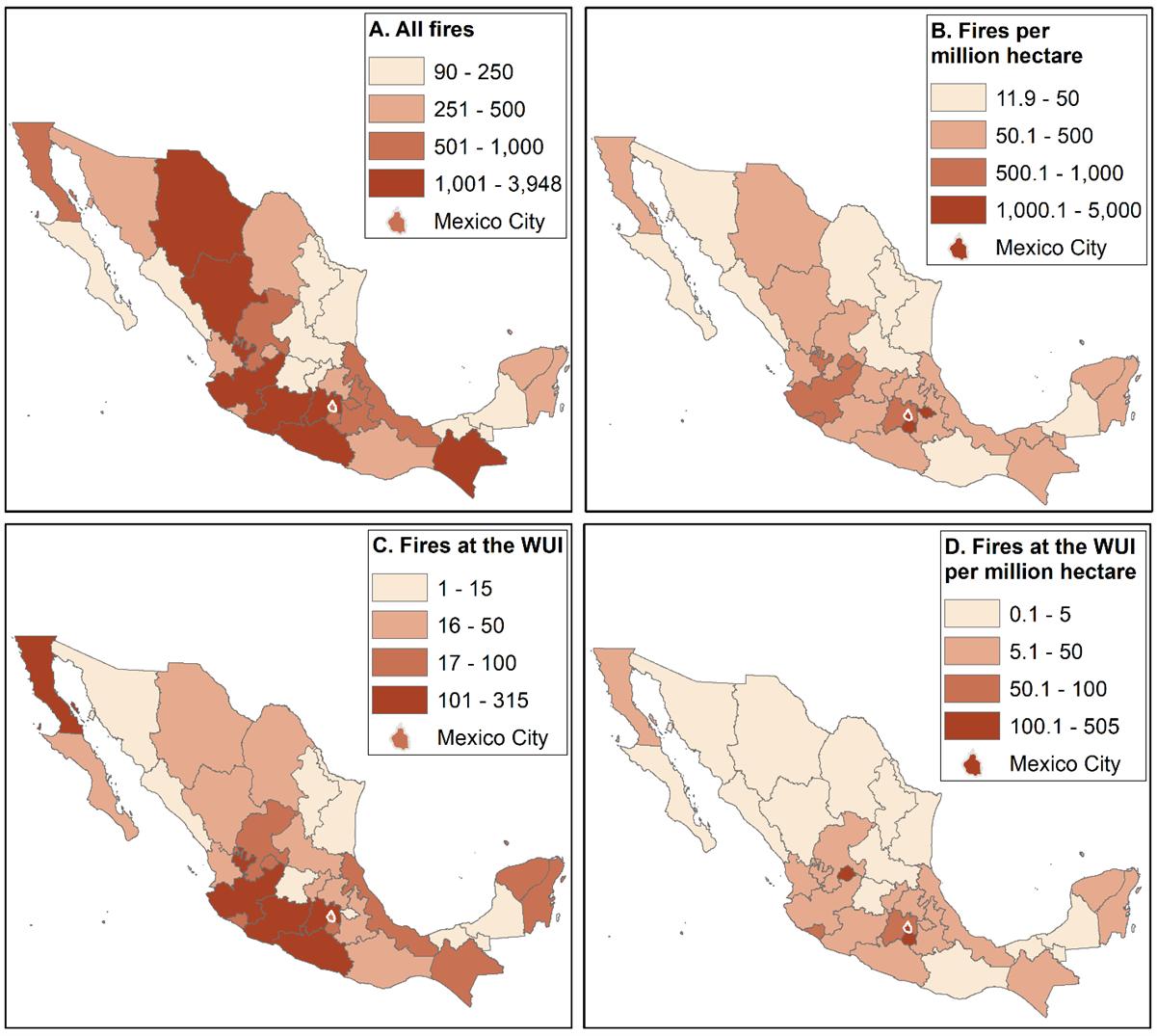

The Mexican National Forestry Commission (CONAFOR), a Mexican agency in charge of forest management, which includes fire registering and reporting has been registering wildfires for the past eleven years across the country. It has recorded 24,851 fires between 2010 and 2020 across the Mexican territory. The total number of fires may not tell the whole story; it is thus important to explore the extent to which fires occur at the WUI. To do so, we combined the CONAFOR fire dataset with our own identification of WUI areas in Mexico for the period 2010-2020. We combined this data using a Geographic Information System (ArcGIS version 10.3). Our methodology is summarised in Figure 1 and is detailed in our publication [27]. Our analysis shows that 4% of fires occur entirely within the WUI, and an additional 5% occur in the WUI as well as in rural and/or urban areas. This means that although the WUI represents less than 4% of the Mexican territory, up to 9% of fires impact the WUI. This proportion rises to 11% for the 2019-2020 period. This pattern was also noted in previous studies [24;25]. To illustrate the importance of framing the questions about wildfire prevalence in WUI, Figure 2 presents this varying picture across Mexico. We observe that states across the country (and not only in the north as could be expected) are affected by fire risk at the WUI.

Figure 2. Graphic summary of the methodology taking Aguascalientes City in 2016 as an example.

Figure 2. A) Total number of fires reported by state; B) Total number of fires reported by state, normalised by state size (in million hectares), for purpose of comparison across states; C) Total number of fires at the WUI reported by state; D) Total number of fires at the WUI reported by state, normalised by state size (in million hectares) for purpose of comparison across the states. All data for years 2000-2020 (source: [31]).

Research question 2: Do these wildfires cause societal harm?

Given that we have established the existence of WUI wildfires across the country, we need to understand whether these fires have shown to affect the populations in any way, which may include loss of life, property, injuries or any other economic or social capital loss, including loss of infrastructure pertaining to logistics, energy and water. To determine whether wildfires have caused such harm, we reviewed the Socio-Economic Impact Reports of Disasters in Mexico for the years of 2011 and 2019 and juxtaposed data on fires with that on other disasters.

The first report on the year 2011 [28] stated that the wildfire has been declared the first disaster in the state of Coahuila since 2003, and the impacted area has been greater than any previously recorded since 1998. While no people have died in the wildfires in 2011, 944 were affected. Eight years later (2019), when the last full report of socio-economic effects on population is available on the CENAPRED (Mexico's National Centre for Prevention of Disasters) website [29], chemical emergencies that include wildfires have jumped to the second place among the total loss of human life and loss of property, among which wildfires were responsible for 90.7% of the human life and property loss – a huge increase since 2011. In addition, the report highlights that while a tendency of wildfires occurrence can be seen as lower or fluctuate over years, the affected area is increasing thus making the wildfires more devastating. This conclusion is also supported by 6 reported wildfire-related deaths in Guerrero and Baja California in 2019, where 469 183 people were affected – another increase in wildfire effects compared to the snapshot from 2011. The report also mentions poor construction materials, such as wood and cardboard, as the cause for the loss of property.

Discussion

Our results show that wildfires do occur at the WUI in Mexico. This can likely have adverse impacts on humans (including life and property loss) as the WUI is densely populated. Urbanisation patterns and increased fire occurrence may heighten the risk of wildfire affecting WUI communities in Mexico. Additionally, similarly to other countries, migrations into the WUI (from within or outside the country) may influence development patterns of WUI, potentially sprawling further into the at-risk areas [30]. All these factors combined suggest that less fire-aware individuals will be increasingly moving to fire-prone areas, which can turn into life safety issues in the future.

Limitations

Our method is limited by the quality of our data: The CONAFOR database is only a subset of fires – those that were reported by CONAFOR; and the land use coverage lacks important information such as demographic and built environment characteristics that might be relevant for WUI (see: Stewart, et al., 2007). We acknowledge that the scope of the analysis proposed in this article is limited by the lack of available sources directly related to the problem of the article.

Conclusions

Since wildfire-related effects on humans are preventable, interdisciplinary research efforts including fire engineering, geography, and sociology among others have the potential to contribute to improving wildfire safety. Interdisciplinary approaches are especially important because a wildfire risk is cross-cutting different contexts and scales, meaning that the risk of fire from wildland to urban areas and built environment may affect populations across the socio-economic spectrum differently.

Future studies can explore fire risk to WUI populations adapting the methodology of the WUI in comparison to other countries, involving the population density, types of housing, socioeconomic level, topography and historic period of urbanisation. This work would further contribute to understanding the factors that may limit WUI growth due to topography, WUI development patterns, and other related factors that can contribute to WUI fire risk.

References

[1] Brushlinsky, N. N., Ahrens, M., Sokolov, S. V., & Wagner, P. (2018). World Fire Statistics. CTIF.

[2] UNISDR (2017). Economic losses, poverty & disasters 1998-2017.

[3] IPCC (2018). Summary for Policymakers. In: Global warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty [V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, H. O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P. R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J. B. R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M. I. Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T. Maycock, M. Tignor, T. Waterfield (eds.)]. World Meteorological Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, 32 pp.

[4] McNamee, M., Meacham, B., van Hees, P., Bisby, L., Chow, W. K., Coppalle, A., … Weckman, B. (2019). IAFSS agenda 2030 for a fire safe world. Fire Safety Journal, 110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.firesaf.2019.102889

[5] Ager, A. A., Preisler, H. K., Arca, B., Spano, D., & Salis, M. (2014). Wildfire risk estimation in the Mediterranean area. Environmetrics, 25(6), 384–396. https://doi.org/10.1002/env.2269

[6] Faulkner, H., McFarlane, B. L., & McGee, T. K. (2009). Comparison of homeowner response to wildfire risk among towns with and without wildfire management. Environmental Hazards, 8(May), 38–51. https://doi.org/10.3763/ehaz.2009.0006

[7] Mahmoud, H., & Chulahwat, A. (2018). Unraveling the Complexity of Wildland Urban Interface Fires. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-27215-5

[8] Radeloff, V. C., Hammer, R. B., Stewart, S. I., Fried, J. S., Holcomb, S. S., & McKeefry, J. F. (2005). The wildland-urban interface in the United States. Ecological Applications, 15(3), 799–805. https://doi.org/10.1890/04-1413

[9] de Torres Curth, M., Biscayart, C., Ghermandi, L., & Pfister, G. (2012). Wildland-Urban Interface Fires and Socioeconomic Conditions: A Case Study of a Northwestern Patagonia City. Environmental Management, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-012-9825-6

[10] Modugno, S., Balzter, H., Cole, B., & Borrelli, P. (2016). Mapping regional patterns of large forest fires in Wildland-Urban Interface areas in Europe. Journal of Environmental Management, 172, 112–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.02.013

[11] Ronchi, E., Wahlqvist, J., Gwynne, S., Kinateder, M., Benichou, N., Ma, C., Rein, G., Mitchell, H., Kimball, A. (2020). WUI-NITY: a platform for the simulation of wildland-urban interface fire evacuation. NFPA.

[12] Ronchi, E., Wong, S., Suzuki, S., Theodori, M., Wadhwani, R, Vaiciulyte, S., Gwynne, S., Rein, G., Kristoffersen, M., Lovreglio, R., Marom, I., Ma, C., Antonellis, D., Zhang, X., Wang, Z., Masoudvaziri, N. (2021). Case studies of large outdoor fires involving evacuation. Project Report. International Association of Fire Safety Science-Large Outdoor Fire & the Built Environment Working Group.

[13] Liu Y, Stanturf J, Goodrick S (2010) Trends in global wildfire potential in a changing climate. Forest Ecology and Management 259, 685–697.

[14] Abatzoglou JT, Williams AP (2016) Impact of anthropogenic climate change on wildfire across western US forests. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113, 11770–11775.

[15] Cohen, J. D. (2000). Preventing disaster: home ignitability in the wildland-urban interface. Journal of Forestry, 98(3), 15–21. https://doi.org/http://www.fs.fed.us/rm/pubs_other/rmrs_2000_cohen_j002.pdf

[16] Mutch, R. W., Rogers, M. J., Stephens, S. L., & Gill, A. M. (2011). Protecting Lives and Property in the Wildland-Urban Interface: Communities in Montana and Southern California Adopt Australian Paradigm. Fire Technology, 47(2), 357–377. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10694-010-0171-z

[17] ONU HABITAT (2018). Superficie de CDMX crece a ritmo tres veces superior al de su población. Available at: https://onuhabitat.org.mx/index.php/superficie-de-cdmx-crece-a-ritmo-tres-veces-superior-al-de-su-poblacion

[18] UN (2018). World Urbanisation Prospects. Available at: https://population.un.org/wup/Publications/Files/WUP2018-Report.pdf

[19] SEDATU (2015) Delimitación de las zonas metropolitanas de Me ́ xico, 2015. Available at https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/productos/prod_serv/contenidos/espanol/bvinegi /productos/nueva_estruc/702825006792.pdf

[20] Syphard AD, Sheehan T, Rustigian-Romsos H, Ferschweiler K (2018) Mapping future fire probability under climate change: does vegetation matter?. PLoS ONE 13(8):e0201680. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0201680

[21] Bryant BP, Westerling AL (2014) Scenarios for future wildfire risk in California: links between changing demography, land use, climate, and wildfire. Environmetrics 25:454– 471. https://doi.org/10.1002/env.2280

[22] Rodríguez-Trejo DA, Fulé PZ (2003) Fire ecology of Mexican pines and a fire manage-

ment proposal. Int J Wildl Fire 12(1):23–37. https://doi.org/10.1071/WF02040

[23] Ávila-Flores D, Pompa-Garcia M, Antonio-Nemiga X et al (2010) Driving factors for forest fire occurrence in Durango State of Mexico: a geospatial perspective. Chin Geogr

Sci 20:491–497. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11769-010-0437-x

[24] Monjarás-Vega et al., 2019.. Modeling and mapping fire risk from human factors in

Mexico. In: Proceedings for the 6th International fire behavior and fuels conference.

April 29–May 3, 2019, Albuquerque, New Mexico USA 6

[25] Perez-Verdin G, Navar-Chaidez JJ, Grebner DL, Soto-Alvarez C (2012) Disponibilidad y costos de producción de biomasa forestal como materia prima para la producción de bioetanol. For Syst 21(3):526. https://doi.org/10.5424/fs/2012213-02636

[26] CONAFOR (2010). Incendios forestales. Guía práctica para comunicadores.

[27] Vaiciulyte, S., Rivero-Villar, A. & Guibrunet, L. (2023). Emerging Risks of Wildfires at the Wildland-Urban Interface in Mexico. Fire Technol 59, 983–1006. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10694-023-01376-w

[28] CENAPRED (2012). Características e impacto socioeconómico de los principales desastres ocurridos en la república Mexicana en el año 2011.

[29] CENAPRED (2019). Impacto socioeconómico de los principales desastres ocurridos en México.

[30] Price, O. F., Bradstock, R. A. (2013). The spatial domain of wildfire risk and response in the wildland urban interface in Sydney, Australia. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, 13 (12), 3385-3393.

[31] CONAFOR (n.d) Serie histórica anual de incendios periodo 2010–2020 [online]. Available at https://datos.gob.mx/busca/dataset/incendios-forestales