View the PDF here

AFireTest - Towards fully quantified fire performance

By: Ruben Van Coile, Ghent University, Belgium

The European Research Council (ERC) has granted funding to AFireTest, a 1.5 million EUR research proposal (ERC Starting Grant). Within AFireTest, the research team of Ruben Van Coile from Ghent University aims to develop the necessary methods and tools for a science-based approach to fire testing and fire safety quantification. A concept of "Adaptive Fire Testing" will be developed whereby fire tests are adapted to the specifics of the building product and its application, allowing for detailed insight in fire performance. An ERC grant is considered very prestigious as the ERC funds breakthrough, high-risk/high-gain research in any field.

Problems with the current approach to fire testing and fire safety design acceptance

Sustainability and energy-efficiency are quickly transforming the built environment. High performance glazing, cross-laminated timber and other innovations are changing the way we build. Currently, we assume that our existing standardized test methods and design prescriptions are sufficient to ensure that our new green buildings will also be fire safe. However, key standardized test methods have never been developed with a view on characterizing innovative 21st century construction products[i], and our design prescriptions are mainly based on learning from disasters[ii]. Thus, currently the main approach to ensuring fire safety in buildings is a strategy of "wait and see". Such an approach may have been reasonable in times of relatively slow innovation, and for situations where the consequences of failure are limited. For innovative building materials and integrated complex buildings, however, adequate fire performance should be explicitly demonstrated[iii].

The explicit evaluation of fire safety performance is the realm of performance based design (PBD), i.e., demonstrating safety by calculating fire performance from scientific and engineering principles for a specific design configuration[iv]. There are however important obstacles to the application of PBD[v]. Notably, there is an absence of appropriate input data for calculation models. While standardized testing is the go-to-strategy for obtaining data, these tests have not been developed to provide the data necessary for PBD (e.g., thermal properties for natural fire exposures). There are also difficulties with the acceptance of PBD by oversight bodies (the Authority Having Jurisdiction, or AHJ) due to asymmetry in expertise and resources[vi]. This limits the ability of AHJs to handle both an increasing number and an increasing complexity of PBD approvals as innovative products and designs are being brought to market.

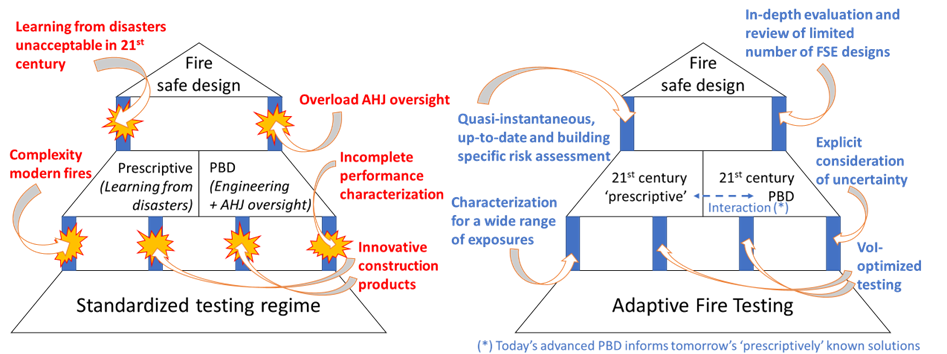

Considering the above, the 20th century approach for achieving a fire safe design is losing stability (Figure 1, left). In summary, the following fundamental issues have been highlighted:

(i) The current prescriptive design approach based on standardized testing is ill-adapted to accommodate for innovation in the construction industry;

(ii) Current standardized fire testing procedures do not provide the necessary input for robust performance-based design.

(iii) The current approach to (governmental) fire safety design verification is not capable of handling a surge in the quantity or complexity of performance-based designs.

Figure 1 – Left: 20th century paradigm for achieving fire safe design losing stability due to built environment innovation; Right: 21st century paradigm for achieving fire safe design, based on Adaptive Fire Testing.

Vision for a new approach

Adaptive Fire Testing

A paradigm shift is necessary to bring fire safety into the 21st century. As a foundation for this paradigm shift, the concepts underpinning fire testing need to be fundamentally revisited so that fire tests provide the necessary data for the next generation of fire safety designs (both 21st century PBD, as well as a new generation ‘prescriptive approach’). Fire tests need to be conducted with a view on maximizing the information gain from the tests, and must take into account the specifics of the material/design. This means stepping away from the limited number of standardized tests with pass-fail criteria, towards adaptive testing whereby the test specifications are set, taking into account (i) the goal of the assessment (ranging from fundamental material characterization and scientific understanding of fire performance, to demonstrating adequate safety for a specific end-use); (ii) the prior uncertainties regarding the construction product response; and (iii) the expected net benefit (i.e., expected net Value of Information) across feasible fire tests. In other words, the new approach towards fire testing should be one of ‘Adaptive Fire Testing’ whereby fire test specifications are adapted to the goal at hand and the current state-of-knowledge, maximizing the net benefit of performing the fire test.

While the above may appear conceptually straightforward, ‘Adaptive Fire Testing’ is extremely hard to achieve. First of all, the information gain (Value of Information; VoI) from existing fire tests is not quantified. Currently, fundamental knowledge necessary for the VoI evaluation is missing (i.e., material and model uncertainties, predictive models for non-standard fire exposures, and predictive models for the fire performance of advanced construction products), meaning that in depth scientific studies are needed even to allow the development of a proof-of-concept. Secondly, in order to evaluate the optimum test conditions (i) a prior assessment of expected behavior in the test is required, as well as (ii) a framework for defining what configuration is optimal. The necessary prior assessment of behavior has been made possible by the tremendous growth in recent decennia in technical capabilities for the modelling of fire performance. The computational expense of this class of models is, however, of such magnitude that any brute force calculation of prior performance across a wide range of test configurations and uncertain input parameters remains impossible. To overcome this, advanced surrogate modelling (machine learning) approaches beyond the current state-of-the-art in Fire Safety Science and Engineering (FSSE) are required. As black box models have severe drawbacks, grey models should be developed which can be described as “physics-informed surrogate models”. Common machine learning approaches may result in large deviations in the low probability ranges, and therefore fundamental investigations into the development an FSSE-specific grey surrogate modelling approach are needed[vii]. Finally, the framework for defining optimal test configurations must go beyond what is existing in other disciplines, as the efficient specification of additional fire tests depends on the goal of the assessment and the test costs in terms of time, money and environmental impact.

Fire design acceptance in the 21st century

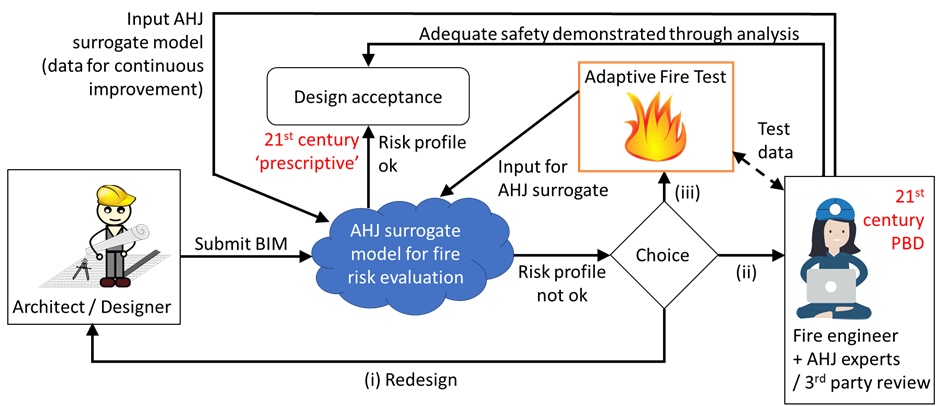

The prescriptive design of the 21st century is envisioned to rely not on predetermined accepted solutions, but on an explicit fire performance evaluation through surrogate models, see Figure 1 (right) and Figure 2. The AHJ maintains an online submission system where architects and designers can upload their designs (e.g., using the format of BIM, Building Information Model). The fire risk of the design is then assessed quasi-instantaneously through the (grey) surrogate model, taking into account the best currently available public data. The obtained risk profile is compared against pre-set thresholds for “prescriptive” design acceptance. The job of the AHJ with respect to prescriptive design acceptance is thus shifted from defining detailed prescriptions (an impossible task in the 21st century) to (i) curating the surrogate model for quasi-instantaneous fire safety performance evaluation, and (ii) setting the acceptance thresholds. Note that in principle the explicit definition of acceptance thresholds is no longer necessary as the surrogate model makes a direct ALARP[viii] (i.e., cost-benefit) evaluation possible; that the curation of the surrogate model can be pooled among AHJ, e.g. on a European level; that AHJ-approved private initiatives may be an alternative; and that the curation also entails continuous improvement (e.g., incorporating the latest research).

If the submitted design does not meet the acceptance thresholds, a number of actions are possible to the architect/designer (Figure 2): (i) the design can be modified, (ii) in case of a design outside the standard scope of the AHJ surrogate model: the performance of the design can be evaluated in depth by a fire engineer using advanced FSSE models, (iii) in case of innovative materials: targeted fire tests can be performed to reduce the uncertainty in fire performance. Naturally, options (ii) and (iii) can be combined. Importantly, upon acceptance the advanced evaluations performed under (ii) and the fire tests performed under (iii) will provide input for next generations of the AHJ surrogate model. To advocate such a radical change in compliance procedures, an in-depth case for its benefit will need to be made, including a comparison against alternative approaches for design acceptance. To be specific, the last point requires an evaluation applying the concepts of the discipline of ‘Law and Economics’ (L&E)[ix], (i.e., the discipline which combines legal and economic theory to evaluate the impact and efficiency of regulatory approaches).

Figure 2 – Fire design acceptance in the 21st century: ‘prescriptive’ design through AHJ-curated surrogate models and PBD informed by comprehensive performance evaluation through Adaptive Fire Testing.

The ERC Starting Grant and the road ahead

The ERC Starting Grant proposal for AFireTest addresses the research needs identified above: (i) Evaluate the information gain (VoI) from fire tests; (ii) Develop an approach for identifying the fire test(s) that maximize(s) the net VoI, taking into account test costs in terms of time, money and environmental impact; (iii) Create an advanced grey surrogate modelling approach, allowing for computationally feasible VoI optimization and quasi-instantaneous design fire safety assessments; (iv) Provide the 21st century conceptualization of “prescriptive design” and “performance-based design”, and develop a comprehensive method to compare advantages and disadvantages of alternative approaches for fire safety compliance and liability (such as increasing governmental oversight within the current framework). While the Adaptive Fire Testing framework is envisioned to be applicable to any type of fire test (e.g., reaction to fire), structural fire performance of modern glazing and load-bearing glass elements will be used as a case study.

The 1.5 million EUR project will run for 5 years, starting in September 2023. The funding allows for three fully funded PhD researchers (4 years each) and two Post-Doctoral positions (3 years each) at Ghent University, Belgium. If successful, AFireTest will provide the tools necessary for a revolution in fire safety testing, and will pave the way for a new fire design acceptance approach based on surrogate models, and advanced PBD[x]

[i] For further discussion, see: Bisby, L. A. (2021). Structural fire safety when responding to the climate emergency. The Structural Engineer, 99(2), 26-27

[ii] This is one of the many important points highlighted in: Spinardi, G., Bisby, L., & Torero, J. (2017). A review of sociological issues in fire safety regulation. Fire technology, 53, 1011-1037.

[iii] Van Coile, R., Hopkin, D., Lange, D., Jomaas, G., & Bisby, L. (2019). The need for hierarchies of acceptance criteria for probabilistic risk assessments in fire engineering. Fire Technology, 55(4), 1111-1146.

[iv] In principle also direct experimental testing can be considered a valid but expensive approach.

[v] Alvarez, A., Meacham, B. J., Dembsey, N. A., & Thomas, J. R. (2013). Twenty years of performance-based fire protection design: challenges faced and a look ahead. Journal of Fire Protection Engineering, 23(4), 249-276

[vi] Spinardi, G. (2019). Performance‐based design, expertise asymmetry, and professionalism: Fire safety regulation in the neoliberal era. Regulation & Governance, 13(4), 520-539.

[vii] For a recently published accessible introduction to machine learning concepts and fire safety, see episode 28 of the Fire Science Show (https://www.firescienceshow.com) and Naser, M. Z. (2022). Demystifying ten big ideas and rules every fire scientist & engineer should know about blackbox, whitebox and causal artificial intelligence. Fire Technology, 58(3), 1075-1085.

[viii] For the interpretation adopted here, see: Van Coile, R., Jomaas, G., & Bisby, L. (2019). Defining ALARP for fire safety engineering design via the Life Quality Index. Fire Safety Journal, 107, 1-14.

[ix] Cooter, R., & Ulen, T. (2016). Law and economics (6th edition). Berkeley Law Books.

[x] To stay up-to-date on progress and hiring: www.linkedin.com/company/sfe-ugent/