View the PDF here

Flexible and Fast Wildfire Modeling Using Public Forestry Data and Uncertainty Estimation

By: Juan Luis Gómez-Gonzáleza, Alexis Cantizanoa, Raquel Caro-Carreterob, and Mario Castroa,c

a Institute for Research in Technology, ICAI School of Engineering, Comillas Pontifical University, Madrid, Spain

b University Institute of Studies on Migration (IUEM), Madrid, Spain

c Grupo Interdisciplinar de Sistemas Complejos (GISC), Madrid, Spain

This article is the short version of the published paper “Leveraging national forestry data repositories to advocate wildfire modeling towards simulation-driven risk assessment”. This is part of a larger project which began at the author’s former institution (Institute for Research in Technology, ICAI School of Engineering, Universidad Pontificia Comillas).

Gómez-Gonzalez, J.L., Cantizano, A., Caro-Carretero, R., Castro, M., 2024. Leveraging national forestry data repositories to advocate wildfire modeling towards simulation-driven risk assessment. Ecological Indicators 158, 111306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2023.111306

1. Introduction and Background

Wildfires are increasingly frequent and severe due to climate change and anthropogenic pressures [1]. Inadequate land management can lead to wildfire scenarios surpassing suppression capabilities [2], posing devastating threats to ecosystems, infrastructure, and human lives [3]. Accurate and timely wildfire modeling is crucial for risk assessment and decision-making [4].

Current wildfire risk assessment relies heavily on indices such as the Fire Weather Index (FWI) [5], which primarily reflect high-risk fire conditions based on meteorological information but neglect landscape heterogeneity, canopy structure variability and susceptibility to fire spread [6], [7], [8]. Fire propagation models integrating dynamic environmental factors and uncertainty quantification are essential tools to address these limitations, [9], [10], [11]. They require good quality input data, consisting on the detailed geographical characterization of fire behavior predictors, such as topography, classification of fuels, canopy structure, and meteorology [12], [13]

This article presents an operational framework (fast, flexible and relying on open forestry public repositories) to prepare the input-data of wildfire simulators, including a modelling approach able to propagate input uncertainties. Our approach enhances prediction accuracy by incorporating canopy variability, meteorological dynamics, and suppression actions, validated on a severe wildfire scenario.

2. Wildfire Modeling Approach

Flexible and fast models are necessary for operational decision-making (e.g. suppression of a fire that escaped initial suppression, devising safe-evacuation routes) and landscape-management (e.g. huge number of simulations to characterize fire susceptibility from fire spread). One of the best existing examples is FARSITE [14], which is capable of modelling fire spread on real landscapes under variable meteorological conditions. However, fast simulators use physical approximations derived from laboratory experiments, leading to inaccuracies in real-world scenarios. Additionally, the dependence on remote sensing techniques to map fire behavior predictors over large landscapes with indirect inference methods introduces input-uncertainty [15]. The adoption of probabilistic approaches helps to reduce these limitations, either through stochastic fire spread rules [16] or ensemble modeling to propagate input uncertainties [17]. A key challenge is integrating diverse forestry datasets into a coherent geographical characterization of fire behavior, given the inherent unpredictability of fire dynamics due to its chaotic and turbulent nature. To address this, we propose improving fire behavior mapping by focusing on input-uncertainty propagation, enabling more reliable uncertainty predictions.

3. Methodology

The fire domain is represented as a raster grid, where fire spread rates are calculated using the deterministic Rothermel model [18]. This model estimates fire behavior based on key predictors, including topography, fuel classification, canopy structure, and meteorological conditions. Each grid cell is assigned an ideal elliptical fire front. Fire growth is simulated using a Cellular Automata (CA) approach [19], in which an ignition within a cell initiates fire propagation toward its eight neighboring cells. Fire spreads along the fastest path determined by local spread rates. Newly ignited cells continue the propagation process, and through successive discrete time steps, the wildfire expands across the landscape.

Fire behavior predictors are derived using a coherent data-pipeline based on standard forestry and remote sensing databases. We focus in the context of Spain because its public forestry service has promoted the development of a series of well-maintained databases, but the methodology outlined here can be used as long as the following information is available:

1. National Orthophoto Program (PNOA): LiDAR data providing detailed 3D forest structure information [20].

2. Spanish Forest Map (MFE): Land cover and vegetation classification [21].

3. National Forest Inventory (IFN): Field data on forest composition and structure [22].

4. Meteorological data from meteorological stations: From the CEAMET meteorological station in the Agrès municipality [23].

This information is then processed to derive the following fire behavior predictors.

1. Canopy Structure Estimation:

o Regression models estimate canopy height (H), canopy base height (CBH), and canopy bulk density (CBD) using LiDAR metrics and IFN field plots.

2. Fuel Models and Topography:

o Land cover data from MFE is combined with LiDAR metrics to assign Rothermel fuel models.

o Digital Terrain Model (DTM) from PNOA data derives height, slope and aspect.

3. Dynamic Wind and Moisture:

o Wind fields are computed using WindNinja [24], considering topography.

o Dead fuel moisture is preconditioned based on weather data using [25].

4. Suppression Modeling:

o Firefighter actions are modeled as barriers preventing fire spread in specific grid cells.

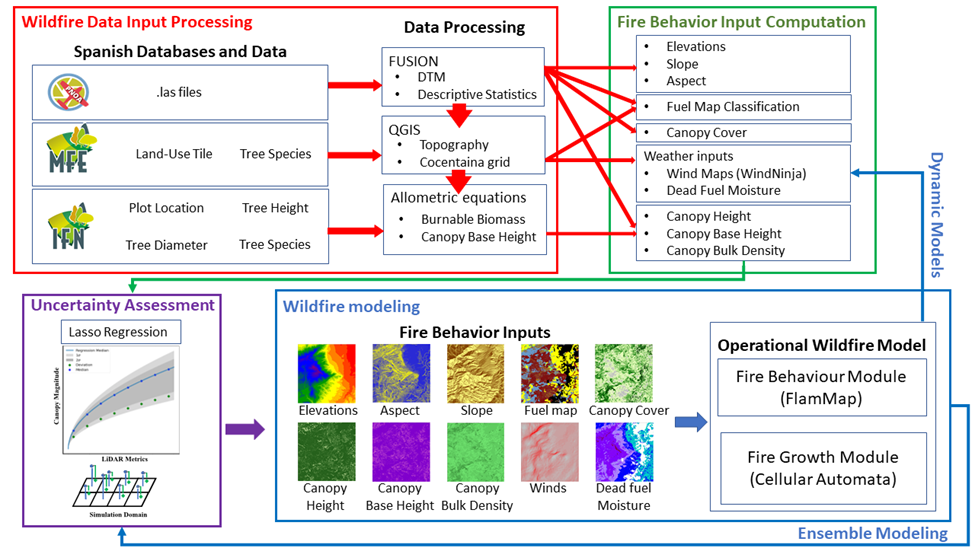

This study performs a detailed uncertainty modelling of the canopy structure magnitudes H, CBH, and CBD. The uncertainty prediction is derived using Lasso regression [26], using canopy data from the IFN as target values and LiDAR statistics restricted to the IFN plots taken as model predictors. Because the uncertainty is not constant across observations, the regression is performed after data linearization, resulting in heteroskedastic uncertainty predictions. Simulation results use the mean regression values with ±2σ deviations in the canopy magnitudes to estimate confidence intervals. Figure 1 outlines the methodology and details the input-parameters modelled for this study.

Figure 1. The diagram illustrates a wildfire modeling framework that integrates Spanish forestry data, such as LiDAR, forest inventory, and land-use maps, with data processing techniques to derive fire behavior inputs (e.g., topography, canopy structure, fuel moisture. Uncertainty assessment allow wildfire ensemble modelling to produce fire perimeter/burnt area confidence intervals.

4. Case Study: Cocentaina Wildfire

The 2012 Cocentaina wildfire in Alicante, Spain, serves as a validation case. The fire burned 545.93 hectares within 24 hours, driven by wind and steep terrain. Suppression efforts included 20 aircraft and 200 personnel [27]. Suppression action is inferred from media reports [28]. Detailed information on the wildfire event is recorded in post-wildfire reports from the wildfire management service from the Region of Valencia [29].

5. Results

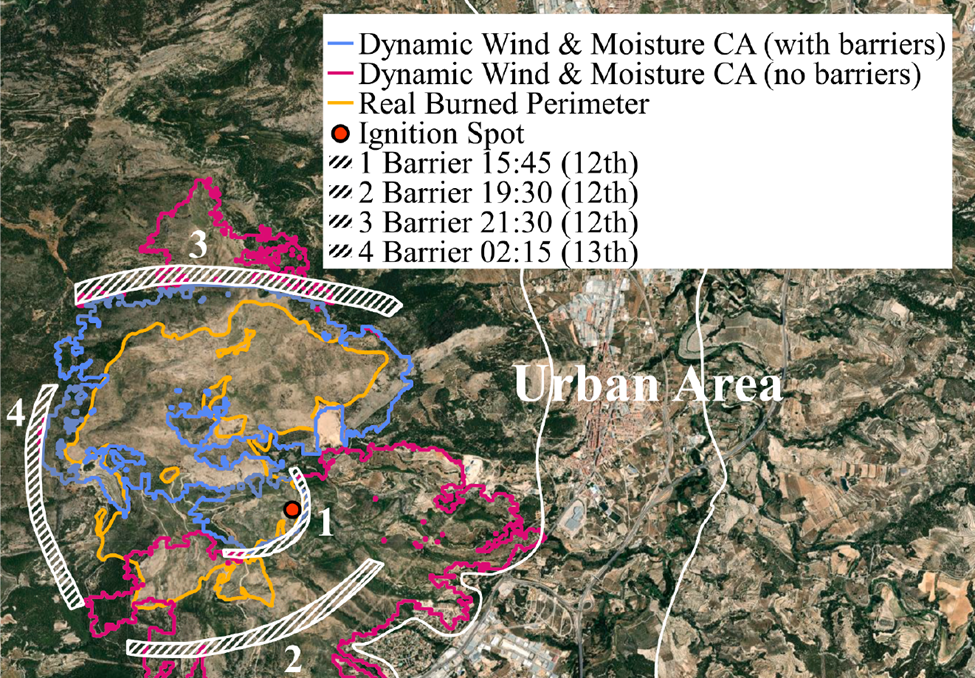

The simulation results presented here model the meteorology variability during the wildfire evolution over a simulated time of 17 hr, for which the real wildfire burnt 90% of the final surface. Results are introduced in terms of the percentage of burnt over-prediction and under-prediction relative to the real final burnt area. Table 1 presents the results for different simulation scenarios and Figure 2 an aerial view of the domain, with the real fire perimeter and simulation results.

5.1 Impact of Canopy Structure and Uncertainty

Consistently, simulations demonstrate that denser canopy configurations reduce fire spread by attenuating near-surface wind speeds and enhancing fuel moisture retention. In contrast, sparser canopies allow stronger winds to reach surface fuels, accelerating fire propagation. This fact highlights the important interaction between vertical vegetation structure and wind profiles, emphasizing that wind is a primary driver of wildfire spread at large scales.

Table 1. Final burned area and percentages of over- and under-burned estimates are presented for static and dynamic models, with and without suppression barriers. Results represent the 95% variability confidence interval derived from canopy structure uncertainty

|

Model scenario

|

Burned Area [,]2σ(ha)

|

Over-burned [,]2σ(%)

|

Under-burned [,]2σ(%)

|

|

Static CA

|

[2079,1951]

|

[286,264]

|

[5,6]

|

|

Dynamic (wind alone)

|

[2166,1625]

|

[312,215]

|

[15,17]

|

|

Dynamic (moisture alone)

|

[1394,1304]

|

[194,179]

|

[38,39]

|

|

Dynamic (wind & moisture)

|

[1546,1325]

|

[201,160]

|

[17,17]

|

|

Dynamic & Barriers (wind alone)

|

[839,640]

|

[81,46]

|

[27,28]

|

|

Dynamic & Barriers (moisture alone)

|

[546,496]

|

[49,42]

|

[49,51]

|

|

Dynamic & Barriers (wind & moisture)

|

[640,584]

|

[46,36]

|

[29,29]

|

Figure 2. Results of the CA with dynamic wind and moisture, without and with barriers. Simulation starts at 15:05 on July 12th 2012, and finishes at 6:30 am July 13th 2012 (17 hr simulation time).

5.2 Static Environmental Conditions

For the sake of comparison, we consider the scenario in which environmental conditions remain static throughout the fire's duration with constant wind speed and moisture content. The model significantly overestimates the final burned area, with an interval from 286% (-2σ in the canopy structure) and 264% (2σ in the canopy structure). The over-estimation is primarily attributed to the models' inability to capture day-night meteorological variations, which led to exaggerated fire spread rates.

5.3 Dynamic Environmental Conditions

When dynamic meteorology is introduced, updating wind fields and fuel moisture at regular intervals based on meteorological observations, burned area estimates improved significantly. Overestimation rates decreased ranging from 201% (-2σ) to 160% (+2σ), demonstrating the importance of accounting for short-term weather variability. Dynamic winds led to greater variability in burned area predictions, ranging from 312% (-2σ) to 215% (+2σ), as the veering of winds increased uncertainty in fire spread. In contrast, dynamic moisture updates produced more consistent results, with overestimation reduced to 145% (-2σ) and 179% (+2σ), as rising moisture levels during the afternoon dampened fire spread. Notably, wind variability alone resulted in lower underestimation (15% (-2σ) to 17% (+2σ)), whereas moisture alone could not accelerate fire spread sufficiently, resulting in underestimations between 38% (-2σ) and 39% (+2σ).

5.4 Suppression Modeling and its Influence

Suppression activities were modeled as fire barriers based on post-fire reports and press releases. When these interventions were incorporated, overestimation rates were reduced to 13%-27%, representing the closest alignment with the observed burned area.

The spatial alignment of suppression barriers with the final fire perimeter indicated that early suppression efforts successfully constrained spread in critical areas. Integrating human intervention in the CA model is mandatory to enhance predictive accuracy particularly in operational settings.

5.5 Model Limitations

Despite overall improvements, some simulations still over/underestimate the burned area. The underestimation is likely to a misclassification of fuel models, indicating the need to incorporate fuel model uncertainty. Overestimations can be partly explained by the absence of a self-extinguishing mechanism in the CA model, a common limitation in wildfire models, which prevents fire from naturally dying out under unfavorable conditions.

6. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that integrating dynamic environmental inputs, uncertainty quantification, and suppression actions into ensemble wildfire modeling significantly improves prediction accuracy. The Cocentaina wildfire case study highlighted the limitations of static models, which tend to overestimate burned area, while dynamic models better capture day-night weather variability and suppression impacts.

Canopy structure uncertainty was shown to influence fire spread predictions, emphasizing the need for accurate vegetation characterization. Ensemble modeling provided confidence intervals, enabling fire managers to assess best- and worst-case scenarios for more informed decision-making.

The proposed framework, leveraging public forestry data and a CA-based propagation model, offers an adaptable tool for generating customized fire behavior cartography. Future work should extend uncertainty modeling to fuel classification and wind fields, while addressing self-extinguishing processes and fire-wind interactions.

References

[1] M. W. Jones et al., ‘State of Wildfires 2023–24’, Jun. 13, 2024. doi: 10.5194/essd-2024-218.

[2] M. R. Kreider, P. E. Higuera, S. A. Parks, W. L. Rice, N. White, and A. J. Larson, ‘Fire suppression makes wildfires more severe and accentuates impacts of climate change and fuel accumulation’, Nat Commun, vol. 15, no. 1, p. 2412, Mar. 2024, doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-46702-0.

[3] D. M. J. S. Bowman, G. J. Williamson, J. T. Abatzoglou, C. A. Kolden, M. A. Cochrane, and A. M. S. Smith, ‘Human exposure and sensitivity to globally extreme wildfire events’, Nat Ecol Evol, vol. 1, no. 3, p. 0058, Feb. 2017, doi: 10.1038/s41559-016-0058.

[4] A. W. Dye, P. Gao, J. B. Kim, T. Lei, K. L. Riley, and L. Yocom, ‘High-resolution wildfire simulations reveal complexity of climate change impacts on projected burn probability for Southern California’, fire ecol, vol. 19, no. 1, p. 20, Apr. 2023, doi: 10.1186/s42408-023-00179-2.

[5] M. J. Erickson, J. J. Charney, and B. A. Colle, ‘Development of a Fire Weather Index Using Meteorological Observations within the Northeast United States’, Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology, vol. 55, no. 2, pp. 389–402, Feb. 2016, doi: 10.1175/JAMC-D-15-0046.1.

[6] A. Benali et al., ‘Deciphering the impact of uncertainty on the accuracy of large wildfire spread simulations’, Science of The Total Environment, vol. 569–570, pp. 73–85, Nov. 2016, doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.06.112.

[7] M. Kelly et al., ‘Impact of Error in Lidar-Derived Canopy Height and Canopy Base Height on Modeled Wildfire Behavior in the Sierra Nevada, California, USA’, Remote Sensing, vol. 10, no. 1, 2018, doi: 10.3390/rs10010010.

[8] M. C. Kennedy, S. J. Prichard, D. McKenzie, and N. H. F. French, ‘Quantifying how sources of uncertainty in combustible biomass propagate to prediction of wildland fire emissions’, Int. J. Wildland Fire, vol. 29, no. 9, p. 793, 2020, doi: 10.1071/WF19160.

[9] A. L. Sullivan, ‘Wildland surface fire spread modelling, 1990 - 2007. 1: Physical and quasi-physical models’, Int. J. Wildland Fire, vol. 18, no. 4, p. 349, 2009, doi: 10.1071/WF06143.

[10] A. L. Sullivan, ‘Wildland surface fire spread modelling, 1990 - 2007. 2: Empirical and quasi-empirical models’, Int. J. Wildland Fire, vol. 18, no. 4, p. 369, 2009, doi: 10.1071/WF06142.

[11] A. L. Sullivan, ‘Wildland surface fire spread modelling, 1990 - 2007. 3: Simulation and mathematical analogue models’, Int. J. Wildland Fire, vol. 18, no. 4, p. 387, 2009, doi: 10.1071/WF06144.

[12] E. Aragoneses, M. García, P. Ruiz-Benito, and E. Chuvieco, ‘Mapping forest canopy fuel parameters at European scale using spaceborne LiDAR and satellite data’, Remote Sensing of Environment, vol. 303, p. 114005, Mar. 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2024.114005.

[13] European Fuel Map (EFFIS), ‘European Fuel Map, 2017, based on JRC Contract Number 384347 on the “Development of a European Fuel Map”, European Commission’. 2017. Accessed: Jan. 10, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://effis.jrc.ec.europa.eu/applications/data-and-services

[14] M. A. Finney, ‘FARSITE: Fire Area Simulator-model development and evaluation’, Res. Pap. RMRS-RP-4, Revised 2004. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 47 p., vol. 4, 1998, doi: 10.2737/RMRS-RP-4.

[15] M. E. Alexander and M. G. Cruz, ‘Limitations on the accuracy of model predictions of wildland fire behaviour: A state-of-the-knowledge overview’, The Forestry Chronicle, vol. 89, no. 03, pp. 372–383, Jun. 2013, doi: 10.5558/tfc2013-067.

[16] J. M. Morales, M. Mermoz, J. H. Gowda, and T. Kitzberger, ‘A stochastic fire spread model for north Patagonia based on fire occurrence maps’, Ecological Modelling, vol. 300, pp. 73–80, Mar. 2015, doi: 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2015.01.004.

[17] M. A. Finney et al., ‘A Method for Ensemble Wildland Fire Simulation’, Environ Model Assess, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 153–167, Apr. 2011, doi: 10.1007/s10666-010-9241-3.

[18] P. L. Andrews, ‘The Rothermel surface fire spread model and associated developments: A comprehensive explanation’, Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-371. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 121 p., vol. 371, 2018, doi: 10.2737/RMRS-GTR-371.

[19] A. Alexandridis et al., ‘Wildland fire spread modelling using cellular automata: evolution in large-scale spatially heterogeneous environments under fire suppression tactics’, Int. J. Wildland Fire, vol. 20, no. 5, pp. 633–647, Aug. 2011, doi: 10.1071/WF09119.

[20] Spanish National Geographic Institute (IGN), ‘PNOA LiDAR First Survey’. IGN download center, 2008. [Online]. (Available on 26-02-2025: https://centrodedescargas.cnig.es/CentroDescargas/locale?request_locale=en)

[21] Ministry for the Ecological Transition and the Demographic Challenge (MITECO), ‘Spanish Forestry Mapping (MFE)’. Dec. 2005. [Online]. (Available on 26-02-2025: https://www.miteco.gob.es/es/cartografia-y-sig/ide/descargas/biodiversidad/mfe_ComunidadValenciana.aspx)

[22] Ministry for the Ecological Transition and the Demographic Challenge (MITECO), ‘Spanish National Forest Inventory (IFN)’. 1997. [Online]. (Available on 26-02-2025: https://www.miteco.gob.es/es/biodiversidad/servicios/banco-datos-naturaleza/informacion-disponible/ifn3_base_datos_1_25.aspx)

[23] Centro de Estudios Ambientales del Mediterráneo (CEAM) [Mediterranean Center for Environmental Studies], 2025. [Online]. (Available on 26-02-2025: https://www.ceam.es/es/)

[24] N. S. Wagenbrenner, J. M. Forthofer, B. K. Lamb, K. S. Shannon, and B. W. Butler, ‘Downscaling surface wind predictions from numerical weather prediction models in complex terrain with WindNinja’, Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, vol. 16, no. 8, pp. 5229–5241, Apr. 2016, doi: 10.5194/acp-16-5229-2016.

[25] R. M. Nelson Jr, ‘Prediction of diurnal change in 10-h fuel stick moisture content’, Can. J. For. Res., vol. 30, no. 7, pp. 1071–1087, Jul. 2000, doi: 10.1139/x00-032.

[26] H. Zou and T. Hastie, ‘Regularization and Variable Selection Via the Elastic Net’, Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B: Statistical Methodology, vol. 67, no. 2, pp. 301–320, Apr. 2005, doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9868.2005.00503.x.

[27] Ministry for the Ecological Transition and the Demographic Challenge (MITECO), ‘General Statistics on Forest Fires (EGIF)’, 2012. [Online]. (Available on 26-02-2025: https://www.miteco.gob.es/es/biodiversidad/temas/incendios-forestales/estadisticas-datos.aspx)

[28] página-66, ‘Así estamos contando el incendio en Mariola [This is how we are telling the story of the fire in Mariola]’. 2012. [Online]. (Available on 26-02-2025: https://pagina66.com/archive/55681/asi-estamos-contando-el-incendio-en-mariola)

[29] J.L. Soriano-Sancho and M. A. Botella-Martínez, ‘Sistema Integrado de Gestión de Incendios Forestales (SIGIF), Informes Post Incendio Compendio Anual 2012 - 2013 [Integrated Wildfire Management System, Post-Fire Reports Annual Compendium 2012-2013]’, 2015. [Online]. (Available on 26-02-2025: https://prevencionincendiosgva.es/Inicio)