View the PDF here

Evacuation design for preschool facilities

By: Hana Najmanová, Czech Technical University, Czechia

By: Enrico Ronchi, Lund University, Sweden

The evacuation of vulnerable populations is gaining more and more attention in the fire safety engineering domain. Among these groups, preschool-aged children (typically between three and six years old) present unique evacuation challenges related to their movement abilities and behaviours. A set of experimental and survey studies [1], [2], [3], [4] offer a comprehensive overview on this important topic. Drawing on a range of dedicated data collection efforts, they describe the developmental, behavioural, and physical factors influencing how pre-school children respond to emergencies and navigate evacuation routes.

Understanding evacuation behaviour in preschool children requires an appreciation of their developmental stage. During the early childhood, children experience rapid changes across all domains of development (physical, motor, cognitive, and socio-emotional). Preschool children are physically smaller and have different body proportions compared to older children and adults. For example, their average body height increases from around 95 cm at age three to 110 cm at age five. Their body’s centre of gravity is also higher, affecting balance and stability. These characteristics increase the likelihood of falls and influence how they move, especially on stairs. Their walking and running capabilities, while developing rapidly, are not yet fully mature. Children begin to walk around their first birthday but continue refining their gait until around age seven. Running typically emerges a half year after mastering independent walking, it continuously progresses during the preschool years, but it may still not have the same level of coordination and stability seen in older children or adults. Similarly, negotiating stairs presents significant challenges. Young children often use a “marking time” pattern, i.e., they place both feet on each step, a movement which typically requires handrails or adult support.

From a cognitive perspective, the thinking of preschoolers differs significantly from that of adults and children of other age groups. This is typically marked by limited abstract reasoning, reliance on routine, and difficulty in understanding others’ perspectives (known as egocentrism). These traits can hinder children’s ability to independently assess danger or make decisions in unfamiliar situations like an evacuation. During a preschool evacuation, emotionally and socially, children will rely heavily on adults for reassurance and guidance. Their evacuation behaviour is therefore strongly shaped by their relationship with familiar adults, as well as by learned routines from daily life.

Pre-travel phase

One of the most critical known issues is that preschool children rarely initiate evacuation independently in response to alarms. Instead, they require verbal cues or physical prompts from adults to begin moving. This highlights the central role of staff in triggering and managing evacuations and the importance of evacuation drills and training [2], [5]. Pre-travel times are therefore highly variable, ranging from seconds to several minutes. Key influencing factors include:

- The age of the children (younger children typically need more assistance)

- Staff-to-child ratios

- Familiarity with evacuation procedures and routes

Movement Phase

Once in motion, children generally move in structured and supervised formations, i.e., single-file lines, pairs, or compact groups. Their pace is highly dependent on age and physical development. For instance, walking speeds increase with age significantly and range between approximately 0.65 m/s for younger children to values getting closer to adult walking speeds for older pre-schoolers (e.g. 1 m/s and above). On stairs, movement slows significantly. Speeds on stair flights often fall below 1.0 m/s, with younger children requiring more support. Use of handrails is common and sometimes essential, and narrow or steep stairs can become critical bottlenecks. Interestingly, the presence of handrails or adult assistance can also influence children's path choices. Behaviourally, children display a range of physical interactions during movement: hand-holding, playful running, clustering in groups, and hesitancy at unfamiliar obstacles. These interactions can both support and negatively affect evacuation efficiency, depending on the context and supervision quality.

Key evacuation relationships between speed, flow, and density for preschoolers

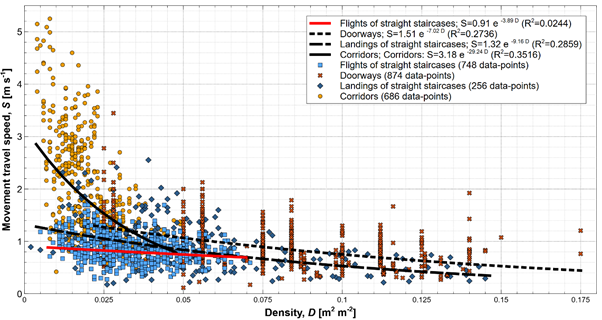

Evacuation modelling traditionally relies on metrics such as walking speed, flow, and crowd density. However, applying adult-based models to preschool children can be misleading. The differences in physical size between children and adults require thoughtful considerations on density units, since using people/m2 may not accurately represent mixed crowds. Research also indicated that children can achieve high travel speeds compared to adults as they tend to run in low-density flat areas [3]. It is therefore important to consider the variability in children's travel speeds across different egress components (see Figure 1). Empirical data show that preschool children can achieve surprisingly high flow rates through exits (even exceeding adult values) due to their smaller body size and minimal personal distances. Nonetheless, these advantages can be offset by behavioural issues, slower stair movement, and the need for supervision.

Figure 1. Relationship between movement travel speed and crowd density for children aged three to seven years on different egress components [3].

Implications for fire safety engineering

The growing body of research on preschool children evacuation has direct implications for fire engineering practice, particularly in the design of early childhood education facilities and the simulation of evacuation scenarios. Given preschool children’s reliance on routine and adult direction, evacuation routes should mirror everyday circulation paths (in line with theory of affiliation [6]). Research supports that fire drills in preschools can be an efficient tool for emergency preparedness if specific aspects of their design, execution, and evaluation are taken into account and if the characteristics, needs, and possible limitations of children are carefully incorporated [2].

From a design perspective, staircases must ideally be appropriately scaled, with lower risers, wider treads, and continuous handrails at child-friendly heights. The occupied area of a preschool child is significantly smaller than that of an adult. While this permits higher occupant densities in modelling, engineers must balance these figures with considerations around psychological comfort, supervision needs, and movement efficiency. Doors on evacuation routes should be designed to allow effective movement, be easy to open for staff and adapted to the needs of children. Self-closing doors in particular can be problematic - firstly, children can have troubles to open them themselves, secondly, staff may have to hold them to allow children to pass.

Standard pedestrian models may in some cases assume independent movement and decision-making. These assumptions fail when applied to preschoolers. Instead, models and model users should incorporate:

- Staff-child groupings and dependencies

- Delayed pre-travel behaviour based on available supervision

- Queuing and stop-and-go effects in movement

- Age-dependent walking speeds, flow capacities, and physical sizes

- Impact of use of handrails during stair movement

As the safety of at-risk populations, such as preschool children, is getting more attention within the fire safety domain, there is a heightened urgency for further research and engineering solutions. This article wants to advocate that we must move beyond “standard” adult-centric models and incorporate the unique behavioural and physical characteristics of a wide range of populations, including young children. Evacuation design for preschoolers is not simply a matter of scaling down. It requires a fundamental shift in how we conceptualise movement, supervision, and behaviour. With continued empirical research and the integration of findings into both architectural design and computational models, the fire safety community can ensure that even the youngest building occupants are protected when it matters most.

References

[1] H. Najmanová and E. Ronchi, “An Experimental Data-Set on Pre-school Children Evacuation,” Fire Technology, vol. 53, no. 4, pp. 1509–1533, Jul. 2017, doi: 10.1007/s10694-016-0643-x.

[2] H. Najmanová and E. Ronchi, “The status quo of fire evacuation drills in nursery schools,” Safety Science, 2025.

[3] H. Najmanová and E. Ronchi, “Experimental data about the evacuation of preschool children from nursery schools, Part II: Movement characteristics and behaviour,” Fire Safety Journal, vol. 139, p. 103797, Aug. 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.firesaf.2023.103797.

[4] H. Najmanová and E. Ronchi, “Experimental data about the evacuation of preschool children from nursery schools, Part I: Pre-movement behaviour,” Fire Safety Journal, vol. 138, p. 103798, Jul. 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.firesaf.2023.103798.

[5] L. Menzemer, M. Marie Vad Karsten, S. Gwynne, J. Frederiksen, and E. Ronchi, “Fire evacuation training: Perceptions and attitudes of the general public,” Safety Science, vol. 174, p. 106471, Jun. 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2024.106471.

[6] J. D. Sime, “Movement toward the Familiar: Person and Place Affiliation in a Fire Entrapment Setting,” Environment and Behavior, vol. 17, no. 6, pp. 697–724, Nov. 1985, doi: 10.1177/0013916585176003.