View the PDF here

Probability of fire in electric vehicles: a new perspective

By: Arnoud Breunese and Kees Both, Etex Group, Belgium

Introduction

The current consensus is that electric vehicles (EV) have a (much) lower probability of catching fire than an internal combustion engine vehicle (ICEV). It is true that EVs, relative to their share of the car population, catch fire less often than ICEVs. However what is overlooked is the fact that the probability of cars catching fire is more or less proportional with the age of vehicles, and EVs are on average much younger than ICEVs.

In this indicative study it was attempted to correct the fire risk for the age of vehicles. The conclusion is then drastically different, with EVs apparently catching fire more frequently than ICEVs. This conclusion is relevant for the future, where EVs are not only expected to become dominant in the car population, but also the average age of EVs will increase towards maturity.

This study is based on limited data, collected through online searching. However, given the relevance of the conclusions, it is recommended to collect more data and analyse in detail the risk of fire of EVs vs. ICEVs while taking into account the age of the vehicle. This will provide important information for future-proof fire protection design of infrastructure such as car park structures.

Proportional relation between fire frequency and car age, for ICEVs

As a starting point, it is important to verify if there is indeed a proportionality between the age of cars and their probability of catching fire. A suitable data source to study the relation between fire frequency and age is the BRANZ STUDY REPORT SR 255 (2011)1. In this report, for the period 1995-2003, per vehicle age group a split-out is given of the share of fires in parking buildings, compared to the share of the overall fleet of registered vehicles.

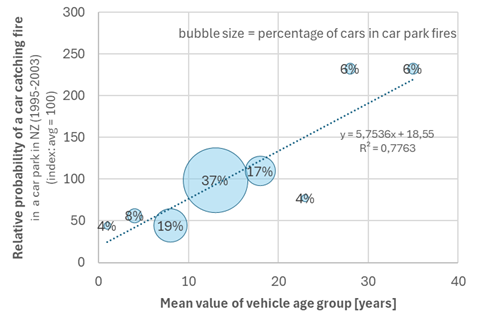

Given the investigated time period, where EVs did not yet exist, we can assume that the cars are ICEVs. When dividing, per age group, the percentage of vehicles involved in a fire in a parking building by the percentage of vehicles of the total fleet, an increasing trend can be observed. The graphical representation of the data is shown in figure 1.

Note that for the sake of graphical representation, a discrete value has been assumed for the average age of cars within a certain age group, e.g. 1 year for the group of 0-2 years. For the group of over 30 years, arbitrarily an average age of 35 years has been assumed. Other assumptions are possible but they do not impact the overall trend and conclusion.

Figure 1: fire probability vs. car age, for parking building fires in New Zealand in 1995-2003

As figure 1 clearly shows:

· The largest age group for cars catching fire in car parks was the age group of 11-15 years old, which in the investigated data is 29% of the fleet and is responsible for 37% of the fires.

· Cars up to 10 years old are 51% of the fleet, but only 31% of the fires.

· Cars of 16 years and older are only 20% of the fleet, but they are responsible for 33% of the fires.

A proportional trendline can be observed between car age and fire probability. The line suggests that a new car has a relative probability of catching fire of 19%, growing to 191% after 30 years (where 100% is the weighted average for the entire population).

As the data only include car fires inside car parks, they cannot be taken as absolute value for the probability of a car catching fire in general. Also, cars of the period 1995-2003 may have different fire probabilities than modern cars, so the data cannot be directly compared with current statistics. However in a relative sense, the trend is clear: there is an increasing relation between the age of ICEVs and their probability of being involved in a fire.

Proportional relation between fire frequency and car age, for EVs

The next step is to verify if also for EVs such an increasing trend can be observed. For EVs, very little information is available. Available data sources include rather detailed statistics from the Netherlands, as well as some reported numbers of fire incidents with EVs in South Korea. The data from the Netherlands are quite detailed, but they have the limitation that the average age of the vehicles did not strongly vary during the reported period (2021-2024). Therefore, it was decided to first investigate the data from South Korea and later on compare these to the data from the Netherlands as validation.

EV fires in South Korea

The National Fire Agency of South Korea keeps track of the number of electric vehicle fires per year. Although a direct publication by NFA has not been found in the desk study, annual numbers for 2018 – 2023 are cited in a news article from 20242. The annual numbers of registered electric vehicles in South Korea can be found on www.statista.com3.

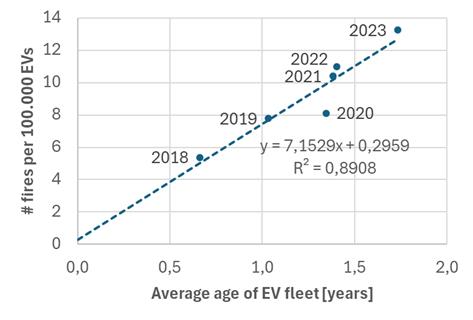

Under the assumption that new EVs are entering the fleet, but no EVs are leaving the fleet, the average age of the EV fleet in each year can be estimated based on the increase of the number of vehicles in the current and preceeding years. This assumption is defendable as EVs are relatively new and the average age of the fleet is unlikely to be strongly impacted by e.g. demolished cars.

For each year we can determine the fire frequency (number of fires/100k vehicles) and the average age of the fleet. When plotting these data for the available years (2018-2023), as shown in figure 2, a clear linear correlation becomes visible. With increasing age of the car population, the frequency of fires increases proportionally, with the trendline almost crossing the origin of the graph.

Figure 2: fire probability vs. average car fleet age, for EVs in South Korea in 2018-2023

Like the data for ICEVs from New Zealand, also the data for EV fires in South Korea clearly show a proportional linear correlation between the average age of the car fleet and the frequency of fires.

EV fires in the Netherlands

In order to validate the conclusions based on the data from South Korea, a similar analysis was done using data from the Netherlands. Detailed reports on fire incidents with electric vehicles are published annually since 2021 by the NIPV (Dutch Institute of Public Safety)4,5. Statistics on vehicle registrations are publicly available on Dutch governmental websites6,7.

With the same approach as used in the analysis of the South Korean data, the average age of the fleet is calculated by weighing the ages of the cars newly added in a given period, under the assumption that no cars disappear from the market due to e.g. demolishing. Also effects of import and export are neglected. This leads possibly to a minor deviation (most likely overestimation) of the average age of the fleet.

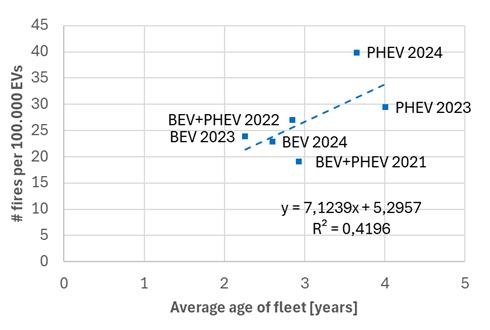

On the dashboard of the NIPV4, consulted on June 6th, 2025, as well as annual publications by NIPV5, data on the number of EV fires are available. In the individual annual reports, individual numbers for BEV’s and PHEV’s can be found, counting cars involved in fire incidents.

Note: The definition in the annual reports is different than in the online database, as the reports count cars on fire and the database counts fire incidents. Incidents with multiple cars on fire can cause discrepancies between both data sets. This seems to be the case for 2021 and 2022, as the numbers of cars far exceed the number of incidents. For the analysis of the probability of car catching fire, the further consequence (spread to more cars in the same incident) is not relevant. Therefore, only for 2023 and 2024, the split between BEV’s and PHEV’s has been used in the analysis, as those numbers approximately add up to the total number of incidents shown on the dashboard.

In table 1, the collected data are combined to calculate the average age of vehicles and fire frequencies in each year 2021 – 2024.

Table 1: fire frequency vs. fleet age for electric vehicles in the Netherlands

|

fleet size

(at mid-year)

|

fire incidents

|

avg. fleet age

(at mid year)

|

fire incidents per 100.000 cars

|

|

year

|

BEV

|

PHEV

|

BEV

|

PHEV

|

BEV

|

PHEV

|

BEV

|

PHEV

|

|

2021

|

309725

|

59

|

2,92

|

19,05

|

|

2022

|

444093

|

120

|

2,85

|

27,02

|

|

2023

|

381486

|

224247

|

91

|

66

|

2,26

|

4,01

|

23,85

|

29,43

|

|

2024

|

494725

|

316016

|

113

|

126

|

2,60

|

3,65

|

22,84

|

39,87

|

The data from table 1 are shown in the graph in figure 3.

Figure 3: fire probability vs. average car fleet age, for EVs in the Netherlands in 2021-2024

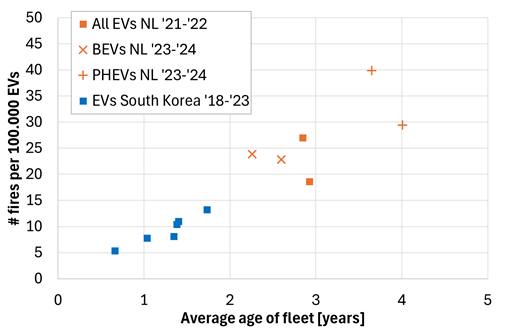

Although there is significant scatter in the data and the variation in average age over the investigated time period is somewhat limited, still an increasing trendline is found. Also when combining the data from South Korea and the Netherlands in one graph, it can be noted that they seem to be roughly on a similar trendline, see figure 4.

Figure 4: fire probability vs. average car fleet age, for EVs in South Korea and in the Netherlands

Fire probability for ICEVs

In order to compare the data for EVs from South Korea and the Netherlands to ICEVs, some statistics on the overall fleet size, fleet age and fire occurrences have been collected and analysed. As those data are a few years old, they will be mostly composed of ICEVs.

The three mentioned data items (fleet size, fleet age and annual fire occurrences) have been found online for four countries: Luxemburg8, Belgium9, the Netherlands10 and Denmark11. Eurostats12 provides numbers for the total number of cars per country per age group. The information from both sources is combined in table 2. To estimate the average age, the number of cars per age group (<2, 2-5, 5-10, 10-20 and >20 years) has been translated into an average age of the fleet by assuming ages of 1, 3.5, 7.5, 15 and 25 years for each of the age groups.

Table 2: information on the full passenger car fleet and fire occurrences for four countries

|

country

|

year of info

|

avg. age of cars (years)

|

#cars (million)

|

#car fires/year

|

#fires/100k cars

|

|

NL

|

2019

|

9,55

|

8,584

|

4941

|

57,6

|

|

BE

|

2015-2019

|

8,49

|

5,799

|

2897

|

50,0

|

|

DK

|

2020

|

8,78

|

2,723

|

1358

|

49,9

|

|

LU

|

2022-2023

|

7,77

|

0,449

|

146

|

32,5

|

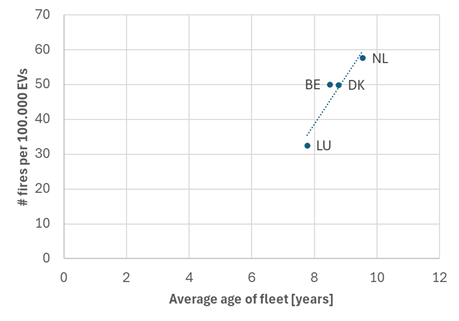

The information on the fire frequency vs. average age is shown in figure 5. Again, we can observe the trend that in countries with an older car population, the fire frequency is higher.

Figure 5: fire probability vs. average car fleet age for all cars (mostly ICEVs) in four countries

Comparing EVs to ICEVs

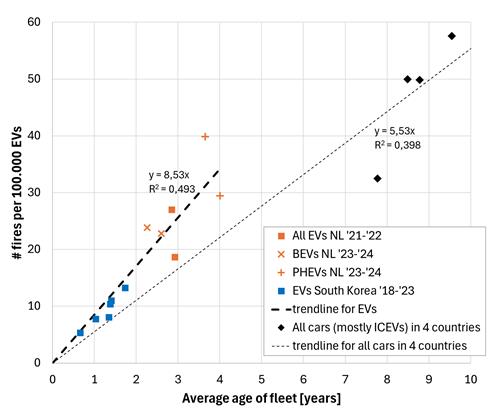

In each of the analyses presented above, an increasing trend was observed between the age of cars and the fire frequency. All of the information is combined in figure 6. Trendlines for ICEVs and EVs have been drawn assuming that they cross the origin (0,0) of the graph.

Figure 6: all collected information about fleet age and fire frequency combined

As figure 6 clearly shows, the data for EVs from South Korea and the Netherlands follow a similar trend, indicated by a dashed line. There are differences between the two countries and between PHEVs and BEVs within the Netherlands, but the trendline generally fits all of these data, indicating that age is dominant in the probability of a car catching fire whereas differences between e.g. BEV and PHEV are of minor influence.

· The trend for EVs (slope of the trendline) is 8.5 fires/100k cars/year per year of fleet age.

· For ICEVs, the slope is 5.5 fires/100k cars/year per year of fleet age.

Arguably the trend may not be linear in reality, so these trendlines and slopes should be seen as indicative only.

Conclusion

Due to the relative new entry of EVs to the market, there is as yet insufficient data to evaluate the fire frequency of EVs at a mature age. Nevertheless, if the current trend continues while EVs gain market share and the population ages further, it is likely that the fire frequency of EVs will eventually become higher than for ICEVs.

It is acknowledged that the analysis is based on limited and fragmented data, as EVs are relatively new in the market and data collection and publication is only just beginning in many countries. Nevertheless, the available data as presented above show a correlation between car (population average) age and fire frequency. Also, the data clearly contradict the current consensus that EVs are less likely to catch fire than ICEVs. This is important for regulators and infrastructure designers to note. As a final note, wherever and whenever more data on EV fires become available, it is important to revisit this first analysis.

References

1. BRANZ STUDY REPORT SR 255 (2011) Car Parks – Fires Involving Modern Cars and Stacking Systems P. Collier 2011 - https://www.branz.co.nz/pubs/research-reports/sr255/

2. https://www.mk.co.kr/en/business/11083232

3. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1097976/south-korea-total-registration-number-of-electric-vehicles/

4. https://kerncijfers.nipv.nl/mosaic/kerncijfers-veiligheidsregio-s/incidenten-met-alternatief-aangedreven-voertuigen.

5. https://nipv.nl/onderzoek/database-incidenten-met-alternatief-aangedreven-voertuigen/

6. https://duurzamemobiliteit.databank.nl/mosaic/en-us/elektrisch-vervoer/personenauto-s

7. https://www.rvo.nl/files/file/2021/02/Jaaranalyse%202020%20-%20Elektrisch%20Rijden%20op%20de%20weg%20Voertuigen%20en%20laadpunten-1.pdf.8. https://www.lessentiel.lu/fr/story/luxembourg-une-voiture-a-pris-feu-sur-l-a3-103327953

9. https://www.lachambre.be/QRVA/pdf/55/55K0061.pdf (p.256)

10. https://www.verzekeraars.nl/publicaties/actueel/aantal-autobranden-blijft-stijgen

11. https://da.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bilbrand

12. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/road_eqs_carage/default/table?lang=en&category=road.road_eqs