View the PDF here

Environmental impact of lithium-ion BESS incidents compared to other types of fires

By: Caroline Gaya, Arnaud Bordes, Anis Amara, Karen Perronnet, Amandine Lecoqo and Benjamin Truchot, INERIS, France

By: Joshua Lamb, Loraine Torres-Castro, Sandia National Laboratories, USA

The following is a reprint of the Executive Summary of a report published by the Fire Protection Research Foundation https://www.nfpa.org/en/education-and-research/Research/Fire-Protection-Research-Foundation/Projects-and-Reports

The usage of lithium-ion batteries is rapidly advancing across various applications, including smartphones, laptops, electric micro-mobility devices, and stationary battery energy storage systems (BESS). Among these, BESS have the unique capability to cover a wide range of energy needs, with capacities ranging from several hundred kWh for residential applications to several MWh in industrial cases. However, the significant onboard energy associated with BESS raises safety concerns, particularly regarding the potential environmental impact of fires. These concerns are especially relevant given the rapid development of the lithium-ion market. If appropriate attention is not given to safety assessments, design selection, and mitigation practices in the rush to keep pace with market demands, the risks of fire (and, in some cases, explosion) could increase. Although notable progress has been made in reducing the failure rates of BESS, the number and scale of these systems have surged dramatically. Consequently, large BESS fires often capture public attention, as seen in the recent Moss Landing fire in January, 2025. Public concern is also growing regarding the potential effects of battery fires on human health and the environment, particularly in terms of air quality, water resources, and soil health. Despite the acknowledgment of these issues, there remains a significant gap in assessing the true impact of such fires on public health.

To assess the environmental impact of BESS fires, it is essential to establish a comprehensive understanding of the potential emissions generated by such incidents. This study, titled “Environmental impact of lithium-ion BESS incidents compared to other types of fires” aims to highlight the current state of knowledge regarding emissions from BESS fires and propose an initial dataset of emission factors specific to these events.

To meet these emissions characterization objectives, the first step proposed for this study was to provide a comprehensive description of a BESS, including an overview of the materials used, their distribution, and their configuration. BESS systems enable the storage and delivery of energy on demand, facilitating the energy balance required by grid-connected systems (e.g., renewable intermittent energy production devices such as photovoltaic systems) or reinforcing the energy grid through peak shaving and responding to user demand. Each BESS system consists of a combination of electrochemical cells that, depending on the chosen configuration, meet specific voltage, current, power, and energy requirements.

BESS Material Composition

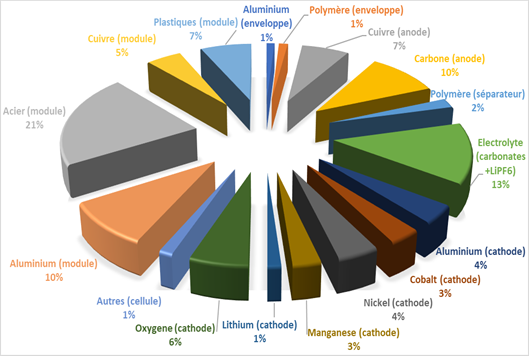

A BESS is composed of two parts: the components related to the electrochemical cells (such as the anode, cathode, electrolyte, and separator), which account for 60 percent of the BESS mass, and those unrelated to the cells [such as the connecting tabs and cables, battery management system (BMS), casing, cooling systems, etc.]. In summary, the main materials that make up a BESS include metallic compounds (which may include nickel, manganese, cobalt, lithium, iron, aluminum, copper, steel); carbonaceous species; binder materials, including PFAS, plastic components [e.g., polyethylene terephthalate (PET)], non-aqueous electrolytes (such as carbon-based solvents with lithium salts that also contain fluorine), and electronic components. It is worth noting that the composition may depend on the specific system, especially in regard to the selected battery chemistry [with lithium iron phosphate (LFP) being the most widely used chemistry in BESS compared to nickel cobalt aluminum (NCA) and nickel manganese cobalt (NMC)].

Figure 1: Material Compositional Breakdown of NMC Lithium-ion Battery.

Emission Pathways and Fire Scenario Development

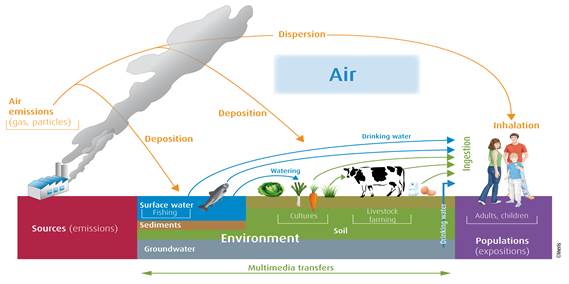

These components, or their degraded forms, can become exposed to the environment once a BESS fire is triggered and can potentially lead to pollution through various pathways:

· Emissions to air (smoke plume sedimentation).

Pollutants carried by the fire or smoke plume can deposit on land and in water, with some dilution over distance. Gaseous emissions to air account for the majority of emissions, however, distributions are heavily weather dependent. Some example species may include acute toxicants, soot, aerosols, particles or organic species, such as VOC, PAH, dioxins/furans, etc.

· Emissions to water (runoff from firefighting activities).

Water used to suppress the fire can transport emissions from damaged batteries into the environment.

· Emissions to soil (fire debris or residue).

Residual materials and contaminants from burnt batteries may contribute directly or indirectly to soil and water pollution after deposition, landfill, or recycling.

Figure 2: Emission Pathways

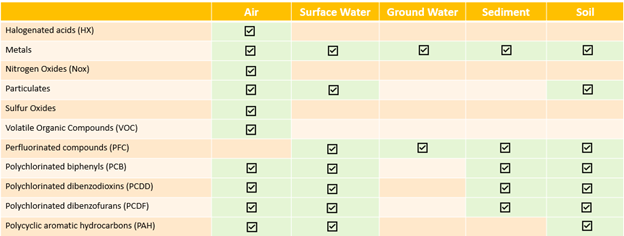

The commonly emitted compounds and particulates released during a LIB BESS fires were found the impact various environmental pathways, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Impacts of common emitted contaminants from BESS fires on various environmental pathways

While these emission pathways are well identified, determining the emissions to be considered for BESS is not trivial, as it depends on multiple parameters (such as the combustion mechanism, particle size distribution, BESS design, and lithium-ion cell composition). Because environmental contamination depends on a fire’s characteristics, defining the fire scenario is a crucial issue. Given that numerous fires have occurred in BESS during the last decade, it makes sense to use lessons learned from those incidents to study the emission pathways. To provide an accurate overview of BESS fires, an analysis of several incidents that offer insights into the environmental impact of BESS fires was performed. Incident reports also provided the opportunity to study the methods used and develop recommendations . For instance, after a fire at a battery recycling facility in Saint-Quentin-Fallavier (France, 2012), no heavy metal pollution was found in the river into which rainwater run-off was poured (most likely due to heavy rainfall dilution). The report for the Perles-et-Castelet fire (France, 2020) noted the need to collect wastewater after the extensive use of water directly onto the container. The BESS fire in Geelong (Australia, 2021) demonstrated a common firefighting method of spraying water around the BESS rather than directly onto the burning container while still collecting the water for treatment. The Morris fire (USA, 2021) led to legal action regarding the release of pollutants into the air and water. The Hwaseong case (Korea, 2024) highlighted the human risks associated with battery fires, as it led to the deaths of 22 people. Meanwhile, the Moss Landing site (USA) has now reported three large incidents in 2021, 2022, and 2025 with reported environmental impacts. As illustrated through the highlighted incidents, there are disparate results and inconsistencies in terms of the claimed environmental impact of BESS fires. While the majority of BESS fire scenarios tend to correspond to failures within a single container, cases of fire propagation and explosion incidents have been reported and should be accounted for. In addition, while heat release rates with BESS fires are moderate compared to similarly sized fires of other types, that does not necessarily mean there is less of an environmental impact, as a high concentration of contaminants tends to be deposited in the immediate vicinity of a BESS fire due to lower smoke dilution. Although many organizations have reported minimal health or environmental impacts following BESS fires, it should be cautioned that many incidents have lacked real-time monitoring. And in some cases, data was collected after plumes dispersed, key pollutants were not captured, baseline data was lacking, or weather impacts were overlooked. Limitations in available data should always be recognized and accounted for when defining the environmental impact of a BESS incident.

Emission Factor Development

To assess the emission factors, a review of scientific literature primarily found data obtained from small-scale cases. Whether these results can be used to predict the effects of larger fires is sometimes questioned; however, these results still provide insightful data and can occasionally be extrapolated to represent larger fires. For instance, a study evaluating extinguishing water pollution after thermal runaway of NMC batteries considered the dilution ratio of real fire cases and highlighted that the pollution could potentially affect nearby water ecosystems based on the concentrations found.

More generally, the state-of-the-art review yielded a broad overview of the pollutants emitted by BESS fires, summarized below:

· Gaseous emissions: Toxic and flammable gases are released during thermal runaway. The composition of the gaseous mixture evolves depending on many factors (such as battery chemistry, state-of-charge, and thermal runaway progression) and may include liquid electrolyte vaporization; carbon monoxide; carbon dioxide; dihydrogen; hydrocarbons (like methane, ethane, ethylene); polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (such as benzene, toluene, styrene, biphenyl); fluorinated compounds (especially hydrogen fluoride and phosphoryl fluoride); and other toxic species such as acrolein, hydrogen cyanide, ammonia, and sulfur dioxide. Notably, the literature review underscores the lack of studies analyzing polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions.

· Aerosol emissions: The aerosols emitted by BESS fires are made up of particles ranging from micrometers to nanometers, combined with liquid droplets. Depending on the battery chemistry, different types of particles have been observed (in terms of morphology, composition, and quantity), resulting in aerosol solid particles composed of a mixture of metallic (Ni, Al, Cu, Co, Mn, and Li) and non-metallic (C, O, F, Si, P, and S) species. The risk of environmental pollution and threat to human life cannot be dismissed, as some aerosol particles contain toxic elements and can be inhaled due to their size. In addition to aerosol particles, solid particles larger than a millimeter were also found.

· Wastewater: Generally, wastewater is loaded with ions, metallic elements, and organic compounds, and the resulting toxicity is significantly affected by the water’s exposure to battery fragments and smoke, as well as by the resulting dilution ratio. Consequently, water pollution greatly depends on the intervention method selected (whether water is applied directly to the battery/system, to the surroundings, or used via an immersion tank). Available studies highlight the potential sources of pollution linked to wastewater.

While the literature provides awareness of the pollution caused by battery thermal runaway, it is difficult to define the lithium-ion battery emission factors due to a lack of large-scale data; insufficient information (e.g., gas concentrations without total emission volume); variations in gas analysis methods; and the wide range of lithium-ion battery (LIB) chemistries and formats considered. Moreover, the absence of mass loss reporting for BESS fires impedes the definition of their emission factors in grams of emitted gas by gram of fuel burned (typically performed in combustion research).

A methodology for calculating LIB emission factors was proposed, normalizing the emission factor to the nominal energy stored (expressed in Wh). The values were normalized based on data provided in literature or by using a generic LIB value (160 Wh/kg for a full battery and 250 Wh/kg for a cell or group of cells without external systems). Three approaches were used to calculate emission factors:

· The emission factors considered for building the database were estimated directly from the scientific papers reviewed, with verification of the measurement methods used and the test conditions performed.

· Emission curves from scientific papers were integrated, when available, to estimate the total amount produced by a given gas. The results were then normalized with the potential available energy based on the sample mass.

· Results from previous in-house studies were also considered.

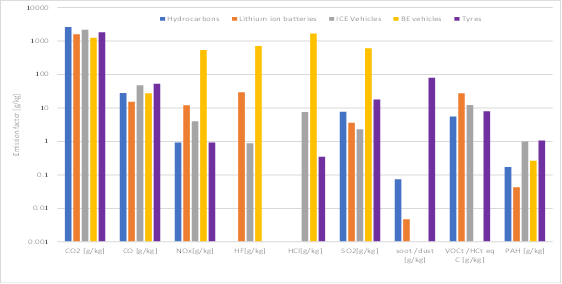

Emission factors for LIBs, obtained using this methodology on the available data, were then compared to those for hydrocarbons, internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles, battery electric vehicles (BEV) vehicles, and tires, leading to the following observations:

· Emission factors for CO and CO2 are not significantly different for LIBs compared to other fuels, such as hydrocarbons, or vehicles (with a cautionary note that the CO/CO2 ratio for LIBs does not directly illustrate the fire ventilation conditions, as LIBs release CO and O2 in vented gases).

· Nitrogen oxide emissions appear to be higher for LIBs (though this requires further investigation). Regarding halogenated acids, as expected, the emission factor for hydrofluoric acid (HF), while not necessarily high, is greater for batteries and BEVs than for ICE vehicles.

o Both halogenated acids and nitrogen oxides (NOx) are particularly concerning as they strongly pollute soil and water and deplete the ozone layer.

· Particle matter production also appears to be lower for LIBs. However, it is important to note that the composition of this particle matter, or more significantly, the particles, likely differs between carbon-based fuels and LIBs, mainly due to the presence of metals in the particle matter from LIBs.

o One of the key potential pollutants with long-term effects for LIBs may be metals. Fire tests underscore a significant emission factor for this type of fuel, much larger than for other fuels, even tires, which are one of the classic fuels with the largest metal emission factors.

o Among the metals found, cobalt and nickel are particularly concerning due to their toxicity to humans and the environment.

· The emission factors for VOCs and PAHs for LIBs seem to be of the same order of magnitude as those observed for other fuels.

These findings are graphically summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Comparative Emission Factors

Summary observations, knowledge gaps and next steps

Several key issues were raised, including the need to clarify the emission factors for each chemical composition of LIBs. In addition, as metallic pollution is a particular concern with LIBs, it was decided that a specific screening of metallic species should be implemented after a LIB fire, as each metal impacts the air and water in different ways. Guidelines were also provided for collecting relevant information for improving emission factors. For instance, continuous gas analysis and mass loss rate measurements were recommended, as were studies dedicated to assessing battery environmental impact. The dependence of emission factors on battery chemistry, triggering methods, and system configurations also warrants further investigation in future studies.

To further study the environmental impact of LIBs, fire modeling based on previously defined emission factors and considering three representative cases was conducted (covering past events and anticipating future potential events with large BESS). The resulting scenarios for LIBs were compared to the same scenarios for hydrocarbons, PVC, and tire storage (for a general overview, as the emission factors remain uncertain). The main findings from the simulations indicated that LIB fires generally have limited thermo-kinetic energy in the fire plume, resulting in reduced atmospheric dispersion. Consequently, PAH and similar product deposits may be higher for a LIB fire than for a classic fuel fire with the same emission factor magnitude, mainly due to this lower atmospheric mixing. In addition, metals appear to be one of the most critical pollutants when considering potential deposits from LIB fires. A cautionary note remains, as these results should be analyzed in light of the difficulties encountered in defining robust emission factors for specific pollutants emitted by LIB fires, particularly metals, which remain a significant unknown parameter in assessing the environmental impact of LIB fires.

As with any fire, BESS fires represent a potential source of environmental pollution. Several pathways exist for contamination, which highly depend on the specific scenario and the firefighting methods used. Emission factors for LIBs were proposed but rely on limited available data. The main conclusion of this study is that the emission of particles containing metallic compounds caused by LIB fires represents a significant concern specific to LIB fires. Other toxic species emissions, such as PAHs and VOCs, were reported and require further analysis. Improvements in measurement and reporting values were suggested for future studies to enhance knowledge on LIB emissions.

While emission factors strongly influence environmental impact, they are not the only parameter. Indeed, the dispersion of the plume is also a critical factor. A particularity of LIB fires highlighted in this study is the limited dilution of the fire plume due to the kinetics involved, which affects the indirect contamination of soil and water. Finally, more extensive analyses of contamination in real cases and large-scale testing are recommended to broaden and gather more consistent data for future environmental impact assessments of LIB fires.