View the PDF here

Do you have a fire door or a fiery door? – Fire load contributions of fire doors and other construction systems

By: Ryno van Wyk and Dirk Streicher, Ignis Fire Testing, South Africa

This article presents a short discussion considering the contribution of doors to heat release rates and fire intensity in an enclosure. The discussions also apply to other construction systems that incorporate combustible material. It is almost inherently assumed that fire doors make a building safer, and this is typically the case. However, what happens if they can also make the fire more intense due to the contribution of their outer combustible skins or core? In a large enclosure with many stored materials, this contribution from doors may be relatively small. However, in a small enclosure, such as a hotel room, it could have a more significant impact, as highlighted below, where the contribution can be approximately 120 kW/m2 or even higher. Hence, this short article presents some musings of fire testing laboratory staff who have observed the impact of tested doors on furnace behaviour and highlight it as a discussion piece.

The purpose of a fire door is to serve as a fire division between two rooms, known as fire compartments. Fire doors are tested in a furnace that complies with EN 1363-1, which describes the requirements for the furnace in which the fire door is tested to maintain consistency throughout testing laboratories. The performance criteria for a fire door are stated in EN 1634-, which outlines the requirements for a fire door to pass based on three criteria: integrity (E) and insulation (I) or radiation (W). The integrity criteria assess any compromise on the door with respect to openings or gaps to allow hot gases to pass through. Insulation and radiation assess the door's ability to provide sufficient insulation to prevent ignition of materials on the unexposed side of the fire door. An element that must carry load is also required to satisfy structural resistance requirements (R).

Based on the criteria mentioned above, fire doors obtain a fire rating that indicates the fire resistance of a specifically tested door assembly. This can typically be a rating such as EI60, which implies that the door passed the integrity and insulation criteria according to the standard for 60 minutes while being exposed to the standard fire curve. According to this result, the performance of any two fire doors with an EI60 rating is the same with respect to serving as a fire division according to the EN standards. However, the standards do not specify the fire performance of a fire door concerning the contribution to the fire severity on the exposed side, i.e., on the fire side. Can a fire door, or other system, influence the fire load in a fire compartment?

Various fire door tests have been conducted at Ignis Testing in a vertical furnace manufactured according to SANS and EN standards, as shown in Figure 1, providing data and experience to analyse the effect of a fire door on the furnace temperature control. The furnace shown is fired using diesel burners, which are controlled with a Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) system to follow the specified standard time-temperature curve. When conducting tests on doors, there have been cases where the door burnt so severely that the furnace burners could virtually be turned off as the door ‘fired’ the furnace. Hence, it was decided that more investigation was required. Benchmark tests were conducted to determine the amount of energy required to heat the furnace to the standard fire curve without any sample – i.e. a blank, relatively inert closure was included to provide very low energy losses. Thereafter, a combustible chipboard door was included because it gave a fire performance similar to some of the doors previously tested (and since no proprietary system could be used). Also, a timber door with a vermiculite core was considered. The latter would normally be considered a good fire door as the non-combustible core limits fire spread and provide a good fire resistance rating.

Figure 1: Vertical furnace and SCADA system at Ignis Testing

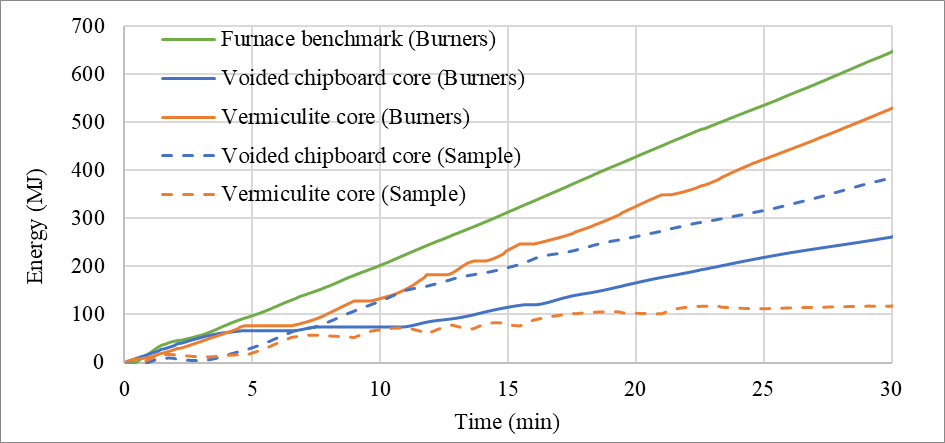

Figure 2 displays the total energy required to heat the furnace to the standard fire curve in three cases: 1) Furnace benchmark – no sample (green), 2) Voided chipboard core – combustible (blue), and 3) Vermiculite core – non-combustible (orange). The furnace is heated with two diesel burners, each with a power range between 100kW and 300kW. The energy input into the furnace is calculated based on the diesel consumption of the diesel burners. The solid lines in Figure 2 display the energy input from the burners for each case. Assuming the benchmark case represents the energy required for no sample heating, the change in energy consumption can be calculated by subtracting each door test's energy consumption from the benchmark test. The dashed line is the difference between the benchmark test and the energy consumption required by the test specimen for each core, respectively. Hence, the dashed curve indicates the total energy that a sample “contributes to the fire”.

Figure 2: Total energy calculated for two fire doors based on a benchmark test with no sample. The solid lines represent the energy input from the burners for each test, respectively. The dashed lines represent the calculated energy contribution, which is the subtraction of the benchmark test and each door test, respectively.

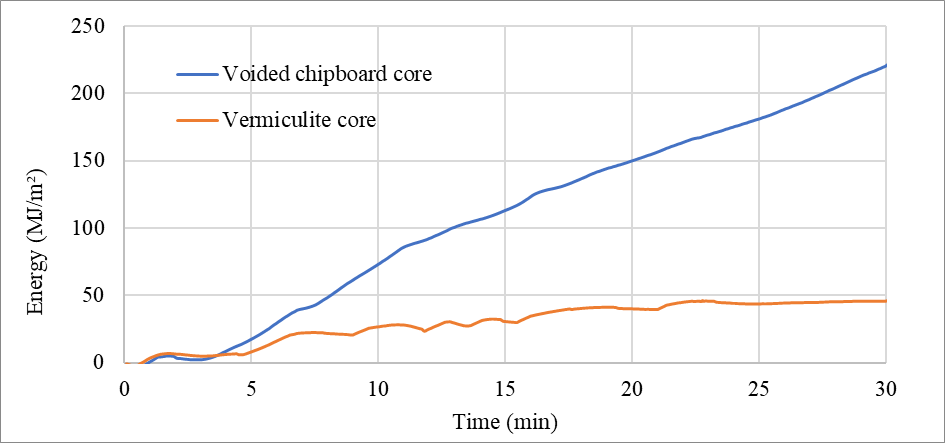

For comparative analysis, the energy contribution per unit area (MJ/m²) for each fire door mentioned above is plotted against each other as shown in Figure 3. From this data, it is clear that the energy contribution for the combustible core is up to four times more than the non-combustible core.

Figure 3: Calculated energy released per unit area comparing fire doors with combustible and non-combustible cores, respectively.

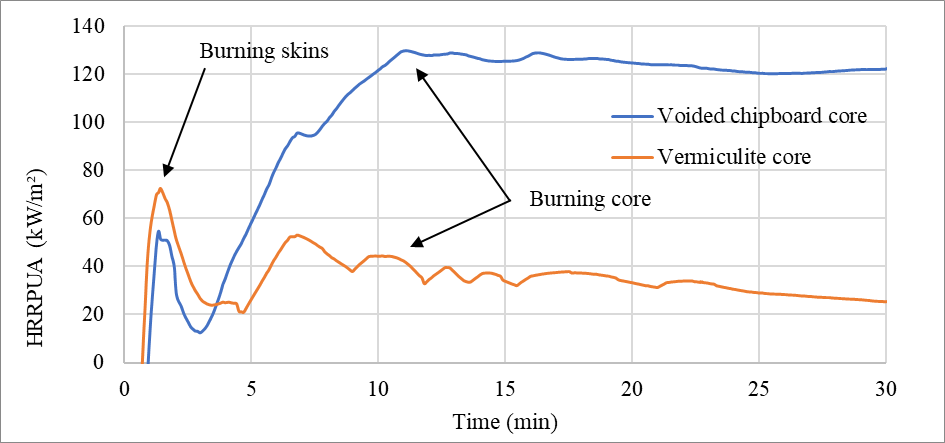

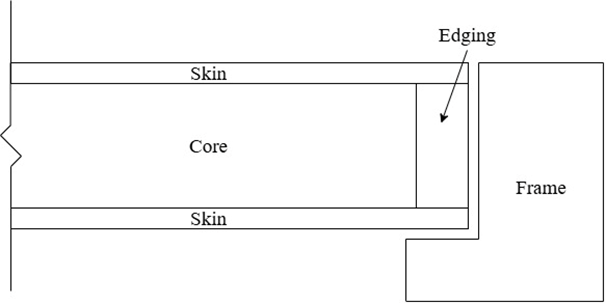

Figure 4 presents the heat release rate per unit area (HRRPUA) calculated for each fire door based on the energy contribution over time. At approximately two minutes, there is a small peak in the HRR; thereafter, the HRR increases to a certain point and remains there until the end of the test. Generally, the core of a fire door is laminated with a combustible skin such as MDF, HDF or commercial plywood, as shown in Figure 5, which presents a cross-section of a typical fire door assembly. In the first three minutes, the skin is heated until it reaches the critical heat flux, resulting in the skin's burning off. Thereafter, the core is exposed to the heat flux in the furnace. Skins produce additional fire load, albeit for a short period and with a low total amount of energy, except that skins produce a localized HRR peak as shown in the graph below. The effect of a combustible core, such as a particle board core, will add a significant amount of additional energy for an extended period. This effect is enhanced when a voided core is used due to the additional surface area of the voids. Additional surface area will increase the total heat release due to the integral of the HRR multiplied by the exposed area. Ultimately, a HRRPUA of 120 kW/m2 for a 2 m2 door leads to a 250 kW contribution to a fire which is not a trivial amount, when design fires may be in the order of 2-5 MW. If there are multiple doors, or double doors, the contribution will increase accordingly.

Figure 4: Total HRRPUA calculated based on the sample energy contribution over time.

Figure 5: Plan view of a cross-section of a typical fire door assembly. The edging is fixed around the perimeter of the core, and the skins are glued on both faces of the door leaf.

In general, the assessment criteria are based on the performance of a fire door on the unexposed side of the fire test. This includes the above-mentioned integrity and insulation criteria, which assess the ability of the fire door to prevent fire spread and to serve as a “fire safe” division between two building compartments. Figure 6 displays photos of the exposed surface (fire side) of a typical non-combustible and combustible fire door. These photos were taken after the skin burned off, and only the core being exposed to the fire. These photos clearly indicate the difference between the flames and fire behaviour of each door on the exposed side of the furnace.

Figure 6: Photos of the exposed face of a typical non-combustible fire door (left), and a combustible fire door (right).

In conclusion, the fire load contribution of fire doors is not taken into consideration when fire doors are specified for their intended use. Two fire doors with the same fire rating do not necessarily behave the same with regard to the fire load contribution to a fire compartment. The assessment of fire doors according to existing standards also does not take the fuel load of a fire door into account. This work presents a concern regarding some fire doors themselves, with them being the division between fire compartments, while contributing to the fire load. The assessment of the energy contribution of fire divisions could be included in the existing standards, which can be beneficial to a design engineer determining the fire load in a building. The impact of the magnitude of the impact of such door combustibility will range widely depending on the room geometry and fire scenarios considered.