View the PDF here

Understanding pre-movement time and movement speeds in hospital evacuations

By: Paul Geoerg, Akkon Hochschule für Humanwissenschaften, Germany

Luke de Schot, University of Canterbury, New Zealand

Ruggiero Lovreglio, Massey University, New Zealand

This article condenses a study published in Fire Technology (DOI: 10.1007/s10694-025-01731-z)

Hospitals present a distinctive evacuation challenge: many patients are dependent on staff, movement devices, and medical equipment to leave safely, so the time before anyone starts moving (the pre-movement phase) often governs the overall evacuation process [1]. This phase can include critical, but time-consuming, actions such as staff briefing, collecting portable equipment (e.g., portable oxygen), disconnecting patients from monitors, and arranging movement devices like beds or wheelchairs. Consequently, the delays associated with preparation frequently dominate the total evacuation time. In addition, because patients differ in mobility and level of assistance required, actual movement speeds can vary widely.

Although evacuation models are widely available and increasingly sophisticated, engineers still face challenges in populating these models with inputs for healthcare settings. In particular, valid values for pre-movement time and movement speeds are scarce, leaving practitioners to rely heavily on assumptions or data drawn from very different occupancies, such as offices or residential buildings. This limitation can lead to simulations that underestimate the evacuation time for hospitals, especially in high-acuity areas where patients have more complex medical needs.

Although research by Fahy and Proulx [2], Gwynne and Boyce [3], Geoerg et al. [4], and Lovreglio et al. [5] have provided valuable data on pre-movement time and movement speed, notable gaps remain in assisted-evacuation settings - particularly hospitals, healthcare facilities, and retirement homes - where the combination of patient vulnerability and reliance on staff makes evacuation uniquely challenging.

The aim of our study was to help close this gap by generating new, ward-specific data on both pre-movement and movement phases. Using real hospital evacuation drills conducted across multiple units in New Zealand, we systematically recorded and analysed preparation activities, device use, and evacuation movement speeds. By focusing on actual hospital staff operating in realistic clinical environments, our dataset provides insights that are directly transferable to practice. The intention is not only to enrich the academic understanding of hospital evacuation, but also to supply practitioners with data that they can use immediately when estimating realistic RSET inputs for performance-based design.

How we studied real evacuation drills

We analysed eight announced evacuation drills conducted across two hospitals in 2020, covering four representative clinical areas: a General Ward, a Hyper Acute Stroke Unit, a High Dependency Unit and a Post-Anaesthesia Care Unit. Drills involved simulated patients and on-duty staff, and were recorded with multiple fixed cameras. From the videos, we coded patient-level timelines with clear segmentation into:

1. Staff preparation (briefing or seeking further information);

2. Active preparation (such as movement device preparation and disconnection);

3. Passive preparation (waiting for staff or equipment); and

4. Movement.

The case mix spanned single-bed high-acuity rooms to multi-bed wards and recovery areas, with varying staff-to-patient ratios to reflect different clinical realities.

What we found

Pre-movement times - Across all eight drills, pre-movement was the dominant component of total evacuation time, with travel accounting for only about a quarter to a third of the overall time. The largest share of pre-movement was passive preparation (e.g., waiting for people, equipment, or clearances), while active preparation (e.g., device disconnection and patient set-up), and staff preparation formed the remainder. Averaged across settings, pre-movement was approximately 175 ± 107 seconds. Table 1 presents the experimental data by type of ward. Ward type was an important factor; wards with higher acuity patients had longer and more variable pre-movement times, despite higher staff-to-patient ratios, due to multiple devices requiring safe shutdown and disconnection. Apart from the High Dependency Unit, staff seldom worked strictly on one patient at a time, but instead they alternated between patients, creating staggered cycles of brief active tasks and passive waiting as they coordinated equipment and support.

Table 1 - Total pre-movement time [s] by type of ward

|

Type of ward

|

Number of patients observed

|

Mean

[s]

|

SD

[s]

|

Min

[s]

|

Max

[s]

|

Median [s]

|

|

General Ward

|

17

|

115.0

|

71.4

|

41.0

|

300.0

|

99.0

|

|

Hyper Acute Stroke Unit

|

10

|

172.8

|

94.2

|

36.0

|

314.0

|

185.5

|

|

High Dependency Unit

|

4

|

362.5

|

177.1

|

216.0

|

584.0

|

325.0

|

|

Post-Anaesthesia Care Unit

|

22

|

188.3

|

79.2

|

79.0

|

360.0

|

177.5

|

Evacuation movement speeds - Mode choice produced clear differences in horizontal movement speed. Patient evacuation by bed was the slowest, with mean speeds around 0.67 m/s, reflecting both the mechanical constraints of bed movement and the need for careful navigation. Wheelchair and walking evacuations were faster, averaging roughly 1.19 m/s and 1.07 m/s, respectively. Pooled across all evacuation modes, the mean horizontal speed was about 0.81 ± 0.40 m/s. Table 2 presents the movement speed results by ward type.

Table 2 - Movement speed [m/s] by type of occupancy

|

Type of ward

|

Number of patients observed

|

Mean

[m/s]

|

SD

[m/s]

|

Min

[m/s]

|

Max

[m/s]

|

Median [m/s]

|

|

General Ward

|

17

|

1.06

|

0.45

|

0.33

|

1.98

|

0.99

|

|

Hyper Acute Stroke Unit

|

10

|

0.95

|

0.26

|

0.53

|

1.40

|

0.97

|

|

High Dependency Unit

|

4

|

0.80

|

0.07

|

0.72

|

0.88

|

0.80

|

|

Post-Anaesthesia Care Unit

|

22

|

0.55

|

0.29

|

0.13

|

1.08

|

0.50

|

Why it matters for fire safety

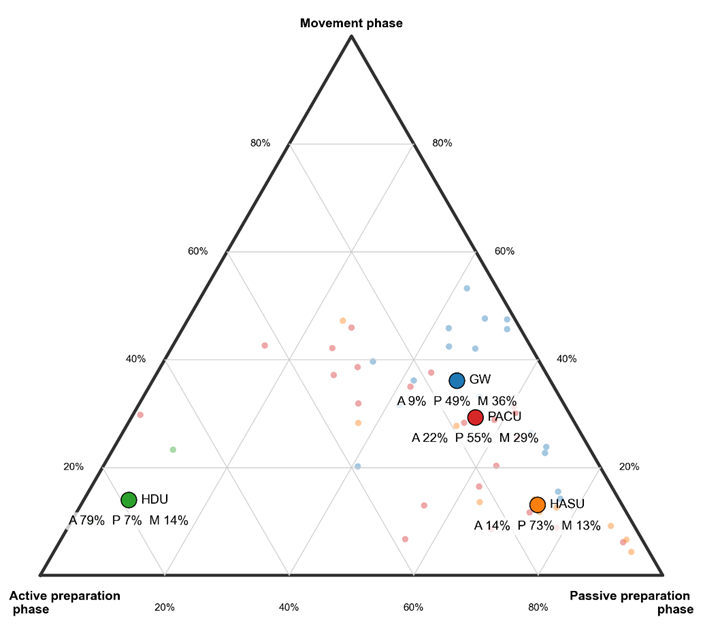

The findings point to several actionable considerations for performance-based design in healthcare occupancies. Because passive preparation was often the single largest contributor to total evacuation time (Figure 1), the most impactful interventions are organisational: improving initial staff allocation, pre-staging essential transport equipment (such as wheelchairs and portable oxygen) and formalising early role assignments to reduce idle intervals. In high-acuity wards, like the High Dependency Unit, even generous staffing will not eliminate the time needed for safe device disconnection and patient preparation, which is labelled active preparation in this article. To shorten active preparation time, targeted training is important to ensure staff perform disconnection tasks as efficiently as possible.

Figure 1: A ternary plot showing how evacuation time is divided into three phases: active preparation (staff actions such as disconnecting equipment), passive preparation (waiting or delays before movement), and movement (purposeful movement toward an exit). Each point represents data from an evacuation drill, with the larger symbols showing the median for each hospital ward type. The plot highlights how different wards face very different challenges: for example, patients in the High Dependency Unit spend most of their time in active preparation (79%), while those in the Hyper Acute Stroke Unit spend the majority in passive preparation (73%). By contrast, general ward evacuations show a more balanced mix across all three phases. Abbreviations: A: Active preparation phase, BP: Passive preparation phase, M: Movement phase, GW: General ward, HASU: Hyper Acute Stroke Unit, HDU: High Dependency Unit, PACU: Post-anaesthesia Care Unit.

When developing design scenarios it is important to consider pre-movement times which reflect the type of patient, their associated medical equipment, and their movement devices. Finally, egress modellers should consider the impact of concurrent patient preparation, rather than assuming purely sequential handling, as alternation is a common real-world strategy under resource constraints.

Although our data is collected in New Zealand, the procedures observed (staff preparation, active preparation, passive preparation, and movement) are common across healthcare systems worldwide. Absolute times will vary with staff-to-patient ratios, training, and resourcing, but the overall finding - that pre-movement phases are significant and can dominate evacuation timing - is broadly transferable.

Conclusion

In hospital evacuations, pre-movement time typically dominates over movement time. Pre-movement time can be broken into multiple phases, such as staff preparation time, passive preparation time (waiting), and active preparation time (purposeful work to get a patient ready to evacuate). This distinction between passive and active preparation helps clarify where evacuation times can be reduced, as well as making sure the phases of real evacuation in hospitals are captured. Passive preparation is often far longer than the active preparation, except in High Dependency Units that have high staff-to-patient ratios.

Egress modelling inputs must account for both passive and active preparation times, and these values should be adjusted according to the patient acuity (e.g., acknowledging that High Dependency Unit patients need much longer time to prepare due to their more complex medical equipment).

Overall, this research highlights the sub-components that make up the pre-movement time in hospital evacuation. While this dataset provides useful input for egress modelling, it also lays the foundation for further work to better understand of the factors influencing active preparation, such as the time to disconnect specific types of medical equipment.

References

[1] Geoerg, P., de Schot, L., & Lovreglio, R. (2025). Decoding Hospital Evacuation Drills: Pre-movement and Movement Analysis in New Zealand. Fire Technology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10694-025-01731-z

[2] Fahy, R., & Proulx, G. (2001). Toward creating a database on delay times to start evacuation and walking speeds for use in evacuation modeling. National Research Council Canada.

[3] Gwynne, S., & Boyce, K. (2016). Engineering Data. In SFPE Handbook of Fire Protection Engineering (pp. 2429–2551).

[4] Geoerg P, Berchtold F, Gwynne Steven, Boyce K, Holl S, Hofmann A (2019) Engineering egress data considering pedestrians with reduced mobility. Fire Mater 43(7):759–781. https://doi.org/10.1002/fam.2736

[5] Lovreglio, R., Kuligowski, E.D., Gwynne, S., & Boyce, K. (2019). A pre-evacuation database for use in egress simulations. Fire Safety Journal. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.firesaf.2018.12.009