View the PDF here

Understanding Fire Dynamics in Open Car Parks: Insights from Multiparametric CFD Analysis

By: Wojciech Węgrzyński, ITB, Poland, Jakub Bielawski, ITB, Poland

Danny Hopkin, OFR, UK, Michael Spearpoint, OFR, UK

Introduction

Recent fire incidents in multi-storey car parks have renewed focus on understanding the mechanisms governing fire spread between vehicles and the influence of structural design parameters on fire severity. In recent decade in nearly every year over the past decade there has been a major car park fire, which either resulted in a complete demolition of the structure, or lead to a long repair progress. Previously Tohir et al. (2018), and more recently Miechówka and Węgrzyński (2025) have summarized those in a recent literature review. While several large-scale experimental programmes, including the BRE (2010) study, have provided valuable empirical data, the complexity of vehicle fire development and interaction with the built environment continues to challenge design assumptions. It can be argued that the set of conditions that promote a growth of the fire from a localized event with a few vehicles into a conflagration impacting the building is a topic of continued interest. We attribute those conditions to include car park floor-to-floor height, vehicle occupancy rate, the size of the vehicles, the influence of the external wind conditions. However, we lack a complete explanation on the fire spread mechanisms in large fires, that would provide context on which these variables play a critical role.

Table 1. Examples of large car park fires based on media reports, 2017 – 2024, Miechówka and Węgrzyński (2025)

|

City, Country

|

Approx. number of cars involved

|

Description

|

Year

|

|

Engelen, Netherlands

|

50

|

Under residential complex

|

2024

|

|

Atsugi, Japan

|

100

|

Free standing car park

|

2023

|

|

Munich, Germany

|

29

|

Free standing car park

|

2023

|

|

Luton, England

|

1500

|

Airport

|

2023

|

|

Marsta, Sweden

|

200

|

Residential car park

|

2021

|

|

Warsaw, Poland

|

50

|

Under residential complex

|

2020

|

|

Stavanger, Norway

|

300

|

Airport

|

2020

|

|

Cork, Ireland

|

60

|

Above shopping mall

|

2019

|

|

New York, USA

|

120

|

Kings Plaza shopping mall

|

2018

|

|

Liverpool, England

|

1150

|

Next to a sports arena

|

2017

|

To address the uncertainties, the Fire Research Department at the Building Research Institute (ITB) in Warsaw in collaboration with OFR Consultants in the UK conducted a multiparametric computational fluid dynamics (CFD) analysis to investigate how key geometrical and environmental variables affect fire growth in multi-storey car parks. The study employed the ANSYS Fluent CFD model with automated model creation and data processing scripts, to explore the combined effects of ceiling height, structural bay configuration, arrangement of parked vehicles, and external wind conditions on fire behaviour. The investigated outcomes were predominantly the heat flux at a distance from burning vehicles as this would likely lead to further fire spread.

The research sought not only to enhance the scientific understanding of the phenomenon but was also the first step informing the further development of simplified cellular automata models that could support extensive parametric engineering assessments and regulatory decision-making for multi-storey car parks.

Methodology

The CFD analyses were performed using ANSYS Fluent software (v 19.1), with transient, pressure-based solver with the unsteady Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes (URANS) turbulence model and the Eddy Dissipation Model (EDM) for combustion. Heat transfer through convection, conduction, and radiation was fully resolved using the discrete ordinates radiation model and the weighted-sum-of-gray-gases (WSGGM) approach.

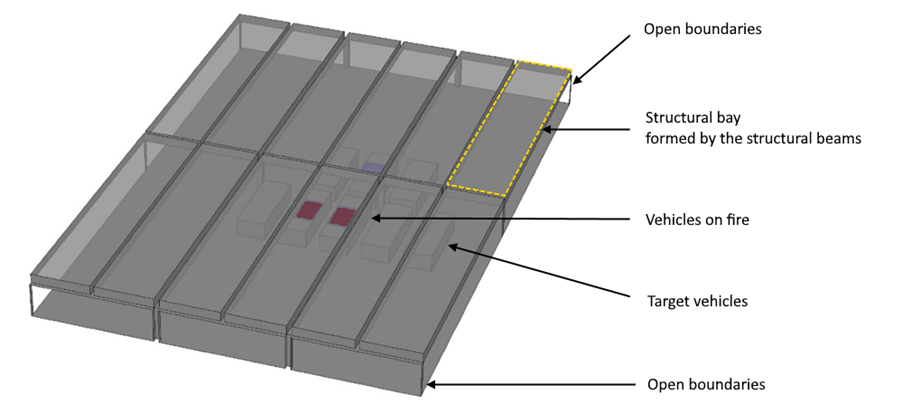

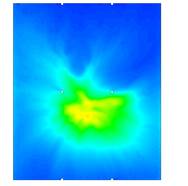

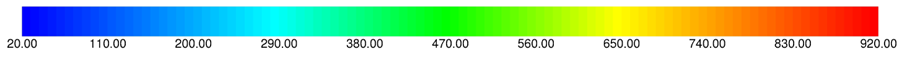

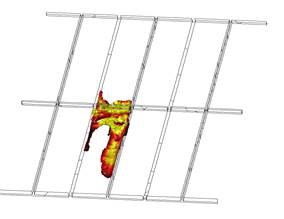

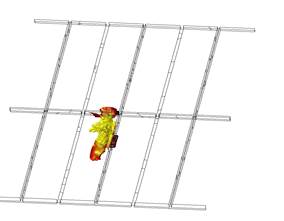

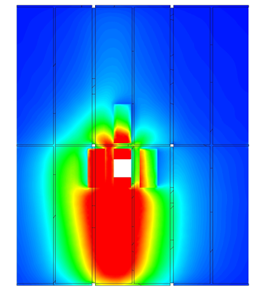

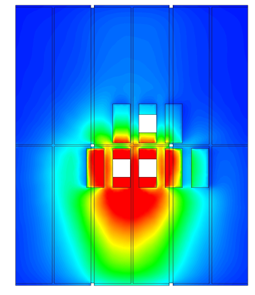

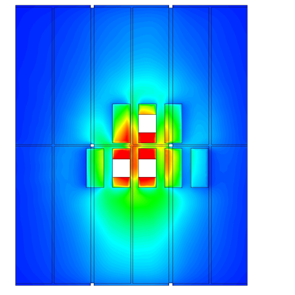

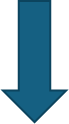

Preliminary calibration of the CFD framework was undertaken against Experiment 1 from the BRE fire spread programme, which investigated heat flux and flame propagation between three passenger vehicles. The CFD model reproduced the experimental geometry and fire development profile, achieving close agreement in peak surface heat flux (CFD: ≈115 kW/m²; experiment: ≈100 kW/m²). While some discrepancies were noted, principally due to simplifications in vehicle geometry, the validation confirmed that the numerical approach could reliably represent the early and fully developed stages of vehicle fires and heat flux distribution from both the vehicle fire plume, as well as the ceiling jets and the hot smoke layer. Some of the simulation findings are illustrated in Figure 1.

Following the calibration, a model of a car park was built representing a typical UK open car park solution, in which we have performed a systematic sensitivity analysis comprising 31 individual transient simulations was performed to evaluate the influence of:

- presence of the structural bays (beamed vs. flat-ceiling configurations),

- location of the parked vehicles in relationship to the structural layout of the beams,

- car park ceiling height (2.5 m – 3.3 m),

- number of burning vehicles (one to three), and

- vehicle orientation (parallel or perpendicular to structural bays).

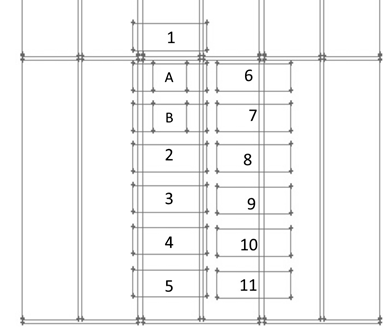

Fig. 1.

(a) numerical model and the distribution of the heat flux in 12th minute of the CFD simulation, (b) comparison of the flame shape in 6th minute of the BRE (2010) experiment with contours of flame (iso-contour of stoichiometric fuel to air ratio) in the corresponding time, (c) at the 21st minute of the BRE (2010) experiment

A simplified representative fire growth was prescribed as a linearly increasing heat release rate (HRR) up to 15 MW over 15 minutes. Boundary conditions simulated open façades typical of naturally ventilated car parks. While the conditions promoting transition to a conflagration were investigated for a range of HRRs, in this short paper we present the most relevant results for chosen values of HRR corresponding to fires which in some circumstances could spread beyond the initial burning vehicles.

Fig. 2. Model of the car park used in the parametric study

Key Findings

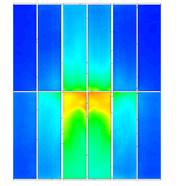

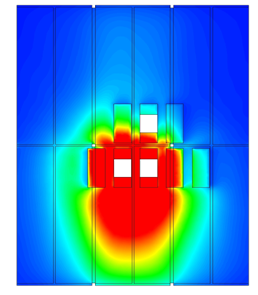

Structural Bay Effect

One of the most significant findings was the structural bay effect - the influence of structural beams in constraining flame extension under the ceiling. This follows a previous observation by Deckers et al. (2013), who observed similar results in relationship with smoke control. CFD results revealed that beams form quasi-compartments in which flames are trapped, leading to elevated ceiling temperatures (up to 920 °C) and heat fluxes exceeding 25 kW/m² towards the floor. When considering classical approach to radiation from fires, as in Heskestad (1983), the heat flux resulting from the flame extension may be higher than the one from the flame, at distances of a few metres.

In contrast, when structural elements were removed and the ceiling was flat, the flames assumed a more axisymmetric form, ceiling temperatures were substantially lower, and radiation to adjacent vehicles decreased markedly. The presence of structural bays thus promotes localized fire severity and enhances the likelihood of lateral fire spread within, rather than between, bays.

|

Under the beam

|

Middle of bay

|

Edge of the bay

|

Flat ceiling

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 3. Temperature of the exposed ceiling surface for different locations of the fire within the structural bay, and compared with the flat ceiling configuration. Results for 8 MW fire

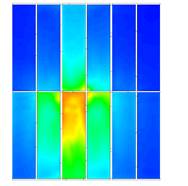

Influence of Ceiling Height

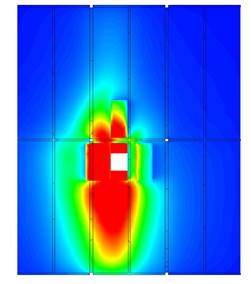

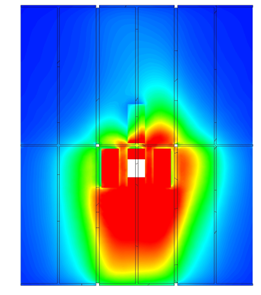

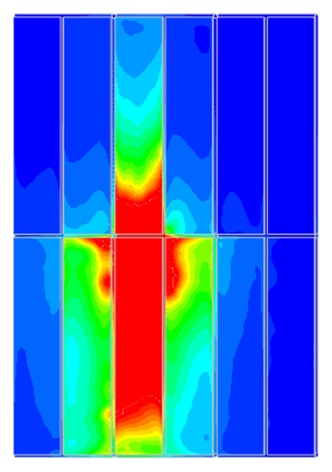

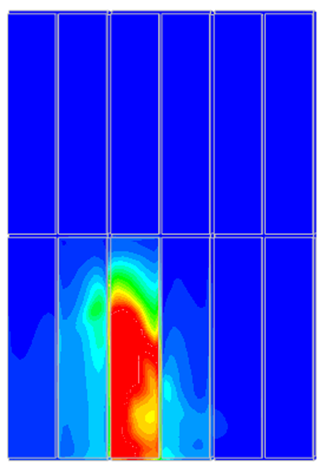

Ceiling height was found to be a dominant parameter in determining whether flames impinge on the ceiling and form a flame extension underneath the ceiling, or there is only a smoke ceiling jet. In low car parks (2.5 m), flames from an 8 MW vehicle fire readily reached the ceiling, producing extensive flame spread beneath structural beams. Increasing the height to 2.9 m or 3.3 m reduced or eliminated this extension, leading to lower surface heat fluxes on the adjacent targets and slower potential fire spread.

This observation supports the hypothesis that in car parks with sufficiently high ceilings, flame extensions are less likely to form, thereby reducing the probability of secondary vehicle ignition. The study illustrates that for a given HRR, the fraction of combustion occurring in the ceiling jet diminishes as height increases, with most heat release confined to the fire plume region.

Table 2 summarizes the HRR at which vehicles up and downstream from those burning, i.e. A and B would ignite assuming a critical heat flux for ignition of 15 kW/m2. The HRR represents the 5th percentile, meaning that in 95% of cases the critical heat release rate to exceed 15 kW/m2 would have been higher.

| a) |

|

|

|

| b) |

|

|

|

|

H = 2.5m |

H = 2.9m |

H = 3.3m |

Fig. 4. Results of the single vehicle fire with HRR of 8 MW with structural elements for car park with height of 2.5 m, 2.9 m and 3.3 m, (a) flame shape, (b) Incident radiation at floor (0 – 25 kW/m²)

Table 2. Critical heat release rates (MW) for car ignition in function of ceiling height (A & B represent the ignited vehicles)

|

Car pos.

|

Range of critical heat release rate [MW] in function of ceiling height (5th percentile)

|

|

2.5 m

|

2.9 m

|

3.3 m

|

|

|

1

|

3.61-4.82

|

3.68-6.59

|

4.46-7.56

|

|

2

|

3.04-4.84

|

3.88-5.73

|

5.06-5.84

|

|

3

|

3.41-5.85

|

4.32-7.13

|

5.69-7.10

|

|

4

|

4.21-6.19

|

4.75-8.00

|

6.15-8.05

|

|

5

|

5.37-6.80

|

5.33-8.58

|

6.32-8.51

|

|

6

|

4.59-5.38

|

5.42-5.91

|

5.19-8.82

|

|

7

|

5.22-5.80

|

5.72-5.96

|

5.68-6.43

|

|

8

|

6.24-6.72

|

5.80-6.57

|

6.44-7.28

|

|

9

|

6.89-7.78

|

7.08-7.94

|

7.18-8.31

|

|

10

|

7.16-8.52

|

7.31-8.53

|

8.34-8.99

|

|

11

|

7.17-10.23

|

7.60-9.43

|

8.58-9.36

|

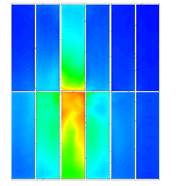

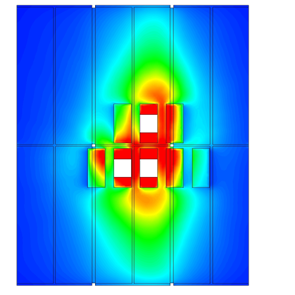

Multiple-Vehicle and Orientation Effects

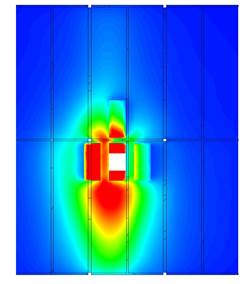

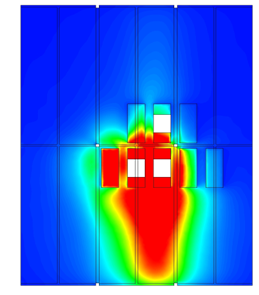

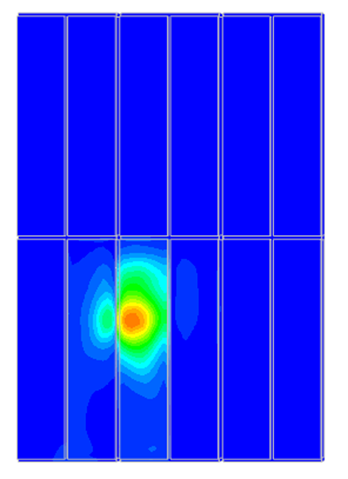

When multiple vehicles burned simultaneously, the distribution of HRR between fire plumes and ceiling jets became spatially complex. A 12 MW scenario involving three vehicles produced a more uniform temperature field but slightly lower peak heat fluxes to the floor than a single 12 MW vehicle fire, as energy was distributed over a larger area.

Vehicle orientation also played a measurable role. Aligning vehicles perpendicular to structural bays led to higher incident heat fluxes on adjacent targets, especially when multiple plumes merged beneath a beam. This indicates that vehicle arrangement relative to the structural frame can materially affect the rate and direction of fire spread. Again, different results were observed for higher car parks, where in general – greater floor to ceiling height resulted in a lower heat flux to the fire surroundings, and less pronounced “bay effect”.

| H = 2.5 m |

|

|

|

|

One vehicle |

Two vehicles |

Three vehicles |

| H = 2.9 m |

|

|

|

|

One vehicle |

Two vehicles |

Three vehicles |

| H = 3.3 m |

|

|

|

|

One vehicle |

Two vehicles |

Three vehicles |

Fig. 5. Results of one, two or three vehicle fire with HRR of 12 MW with structural elements for car park with height of 2.5 to 3.3 m. Incident radiation at floor (0 – 25 kW/m²)

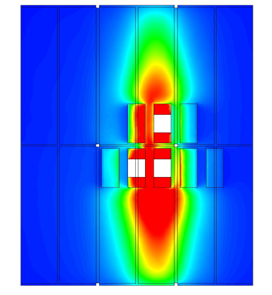

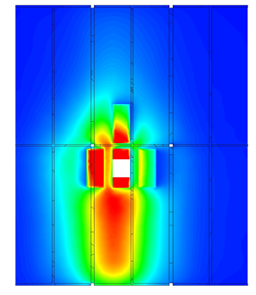

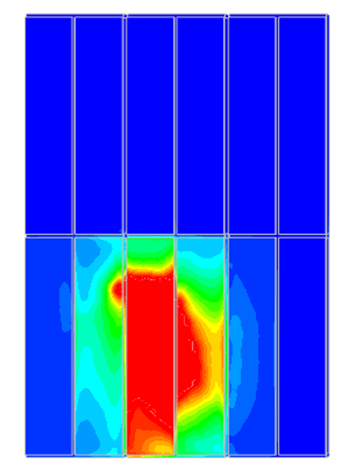

Wind Influence

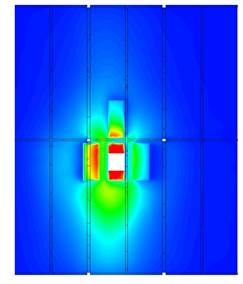

To explore environmental variability, supplementary simulations incorporated external wind velocities of 2, 4, and 8 m/s applied laterally across the car park. Even low wind speeds of 2 m/s significantly altered smoke flow and flame geometry. While increased external wind-induced ventilation generally reduced ceiling-level heat flux—through enhanced mixing of hot gases with fresh air—an external wind also caused flames to tilt and extend horizontally, increasing the likelihood of direct flame contact with neighbouring vehicles.

|

0 m/s

|

2 m/s

|

wind direction

|

|

4 m/s

|

8 m/s

|

|

Fig. 6. Radiation contours on the car park ceiling of 2.5 m height, at 8 MW fire and different wind velocities

Discussion

From the combined analyses, we have observed strong influence of the presence of flame extensions under the ceiling on the resulting potential for fire spread. Four working hypotheses have been formulated related to the governing physical phenomena influencing the presence of this flame extension within open car parks:

- Energy Distribution Hypothesis: For a given geometry, only a limited portion of the total HRR can be accommodated within the fire plume. Excess energy manifests as a flame extension under the ceiling.

- Height-Dependence Hypothesis: Increasing the vertical clearance between vehicles and the ceiling reduces the likelihood of flame extensions and therefore the likelihood of vehicle-to-vehicle spread.

- Bay Confinement Hypothesis: Structural elements that constrain ceiling jets intensify local heating and promote spread within bays.

- Uniformity Hypothesis: Each structural bay may be treated as a quasi-uniform thermal zone, forming a practical basis for simplified analytical treatments or the use of zone models.

These hypotheses collectively provide a framework for understanding and quantifying the interplay between geometry and fire spread mechanisms. Importantly, they suggest that fire severity in open car parks is not solely a function of total HRR, but of how that heat is partitioned spatially within the structure.

The findings lend empirical and theoretical support to the development of simplified zone-based models, in which a car park can be represented as a network of thermally interacting bays. Such models could enable rapid assessment of multiple fire scenarios without the computational expense of full CFD simulations, aiding both performance-based design and regulatory evaluation. The findings of this analysis will be published in the future.

Ongoing research is translating these findings into a parametric zone model capable of estimating fire spread probability and severity in open car parks under varying configurations. Such models could become valuable tools for structural fire engineers, enabling consistent, data-driven evaluation of car park fire resilience without reliance on overly conservative assumptions.

Ultimately, these insights underscore that achieving fire-safe car park design requires an integrated understanding of geometry, fuel load, and environmental conditions—factors that CFD, when carefully calibrated, is uniquely positioned to capture.

References

- McGrattan, K., Miles, S. (2008). Modeling Enclosure Fires Using Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD), in SFPE Handbook of Fire Protection Engineering, 4th ed.

- BRE (2010). Fire Spread in Car Parks. Crown Copyright, London.

- Tohir, M. Z. M., Spearpoint, M., Fleischmann, C. (2018). “Prediction of Time to Ignition in Multiple Vehicle Fire Spread Experiments.” Fire and Materials, 42(1): 69–80.

- Heskestad, G. (1983). “Luminous Heights of Turbulent Diffusion Flames.” Fire Safety Journal, 5(2): 103–108.

- Miechówka, B., Węgrzyński, W. (2025). Systematic Literature Review on Passenger Car Fire Experiments for Car Park Safety Design, Fire Technol. doi:10.1007/s10694-025-01701-5.

- Deckers, X., Haga, S., Tilley, N., Merci, B. (2013). Smoke Control in Case of Fire in a Large Car Park: CFD simulations of full-scale configurations, Fire Saf. J. 57. doi:10.1016/j.firesaf.2012.02.005.