View the PDF here

Fire performance of multi-pane low-energy windows in post-flashover fires

By: Hjalte Bengtsson, Technical University of Denmark, Denmark

This article is the short version of the published paper “Experimental study of the post-flashover fire performance of multi-pane low-energy windows” [1], which is part of a larger research project at the Technical University of Denmark concerning “Low Energy Buildings and Fire Safety” funded by "Grundejernes Investeringsfond" (DK) and "Aase og Ejnar Danielsens Fond" (DK). All publications of the project can be found here: https://orbit.dtu.dk/en/projects/low-energy-buildings-and-fire-safety/

The effect of ventilation conditions on the development of compartment fires is a well-described phenomenon, and the impact on the structural response of a building or on the spread of fire to and from façades can be significant. However, most, if not all, fire models such as the Eurocode parametric fire (EN 1991-1-2, annex A) [2] do not consider that new ventilation openings may be created during the fire as window glass breaks and falls out. This is despite fire-induced glass breakage being identified as an important topic of interest for the broad community of fire engineers and fire scientists all the way back in 1985, when Prof. H. W. Emmons presented at the first IAFSS symposium [3]. It is not for the lack of trying, though. Since Prof. Emmon’s presentation, several studies have investigated window breakage in fires both in relation to the thermal and mechanical effects on the material level (see an overview in e.g. [4], [5], [6]) and to a lesser extent in relation to the derived effects on the fire (see e.g. [7]).

Most of our knowledge and understanding of the performance of windows in fires relate to legacy windows with single or double layers of glass panes. But modern windows should not be expected to behave like these for several reasons;

i. modern windows are typically larger to allow more sunlight into the building,

ii. they need toughened glass to withstand the mechanical forces they experience,

iii. they use low-energy coatings to increase their energy efficiency, and

iv. their cavities between panes are filled with argon instead of air to decrease the conductivity and internal convection.

Additionally, at least in the Nordic regions, modern windows have triple layers of glass panes, and often there is a requirement to use laminated safety glass for personal safety. All these factors affect the fire performance in different ways, but the general trend seems to be that the fire resistance of windows has increased over the last 30 years. In relation to windows, fire resistance means both the time until the window cracks and the amount of glass that falls out of the frame, which then forms the actual ventilation opening.

Despite the overall trend and our knowledge of the important impact ventilation conditions have on fire development, our fundamental understanding of glass breakage in modern windows is still limited. Therefore, we decided to look more closely into the subject through a series of tests conducted at the Danish Institute for Fire and Security Technology (DBI).

Figure 1. Picture from one of the tests showing a hot window in the furnace.

Experimental setup

The experimental campaign consisted of eight tests in total. The parameters investigated were the window size (large or small), the number of glass layers (two or three), and the fire exposure (standard fire or parametric fire). An overview of the tests is seen in Table 1.

Table 1. Overview of the different tests.

|

Specimen ID

|

Size

|

Number of glass layers

|

Fire exposure

|

Repetition

|

|

S-3-B(1)

|

Small

(450 × 450 mm2)

|

3

|

Parametric (B)

|

1

|

|

S-3-B(2)

|

2

|

|

L-2-A(1)

|

Large

(1100 mm × 1100 mm2)

|

2

|

Standard (A)

|

-

|

|

L-2-B(1)

|

Parametric (B)

|

1

|

|

L-2-B(2)

|

2

|

|

L-3-A(1)

|

3

|

Standard (A)

|

-

|

|

L-3-B(1)

|

Parametric (B)

|

1

|

|

L-3-B(2)

|

2

|

The window sizes were decided by the size of the furnace. The number of glass layers reflected more traditional and more modern types of glazing. The fire curves were chosen to reflect common post-flashover fires with the standard fire curve from EN 1163-1 [8] representing a fierce fast-growing fire, and the parametric fire curve based on a typical residential concrete building with a low opening factor of 0.02 m1/2 as described in the Danish National Annex to Eurocode 1 [9] representing a slower and colder fire. The tests did not include the cooling phase of the fire. The temperature-time curves are shown in Figure 4.

All windows were constructed with a wood/aluminium-hybrid frame, and the glazing was made up as follows (described from outside/ambient to inside/fire):

a) Two-layered windows: 4 mm float glass, 16 mm void filled with argon (90 %), 4 mm float glass treated with low-emissivity coating facing the void.

b) Three-layered windows: 4 mm float glass treated with low-emissivity coating facing the void, 18 mm void filled with argon (90 %), 4 mm float glass, 16 mm void filled with argon (90 %), 4 mm float glass treated with low-emissivity coating facing the void.

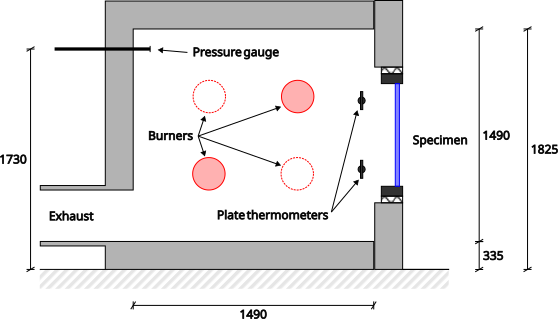

The windows were fitted in a medium-sized fire test furnace as illustrated in Figure 2. The tests ran for up to 30 minutes, but at least until 5 minutes after cracking of the outermost glass pane. During the tests, the glass temperatures, and in two cases the strains at the edges were recorded. The tests were also filmed which allowed for precise measurement of cracking time and for better estimation of glass fallout areas at different points in time after cracking.

Figure 2. Illustration of the test furnace (vertical cross section) with a mounted specimen. The dashed burners are placed on the opposite wall.

Further descriptions of the experimental setup can be found in the original journal paper [1].

Results

In the following, we will focus on the results for the cracking time and the fallout area. More results and details are presented in the original paper [1].

Cracking time

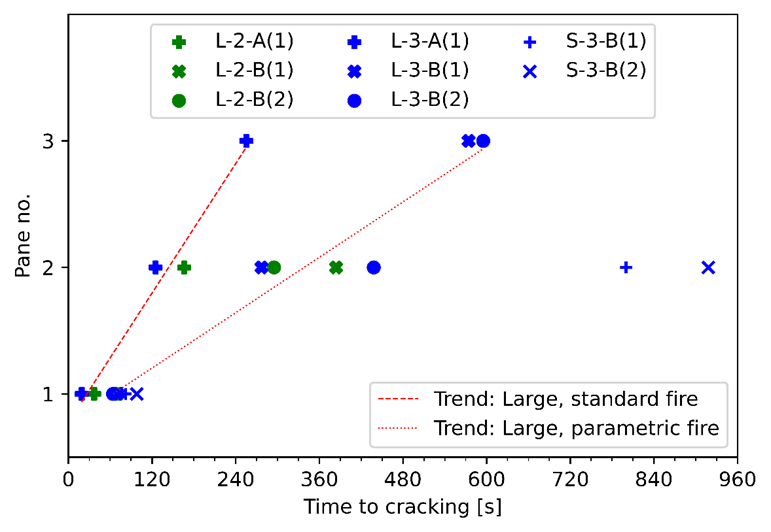

The results for the cracking time for each of the panes in the glazing in the different tests are seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Results for the cracking time for each pane in the tests with different window sizes (S-small or L- Large) different number of panes (2 or 3) and different heating curves (A or B). Note that the third pane in the tests of the small windows (S-3-B(1) and S-3-B(2)) did not crack.

The results show that the panes crack in the order of their placement beginning from the fire side. It is seen that for the parametric fire exposure, the triple layered windows did not have cracking in the outermost until almost 10 minutes after the start of the test, which is almost double the time until cracking of the outmost pane of the double layered windows.

The data suggests that the time between cracking of panes is fixed with the same time between cracking of pane 1 and 2 as between pane 2 and 3. This trend was also seen in the data presented by Peng et al. [10]. This means that the number of panes does not affect the time to cracking of the individual panes. This is seen by the cracking times of the panes following the same linear trend with no regard to the total number of panes. Obviously, having more panes increases the time until all panes have cracked, but the data indicate that the existence of subsequent panes does not impact the cracking time of a given pane.

On the other hand, it is seen that both the window size and the fire intensity have implications for the cracking time. Increasing the fire intensity decreases the cracking times for both the double and triple layered windows. Also, the small windows had a much slower cracking of the second pane compared to the large ones exposed to the same fire curve. Furthermore, the third pane did not crack in the case of the small windows, even though they were exposed to the parametric fire curve for 30 minutes.

We have compared our results of the cracking times for the first (innermost) pane with results for a corresponding calculation in the old software BREAK1 [11] that was developed at Berkeley University in the early 1990’s for calculation of cracking times of single pane glazing. We found that the results BREAK1 did not agree with our test results meaning that the software should not be used to predict cracking in modern low-energy windows.

Fallout area

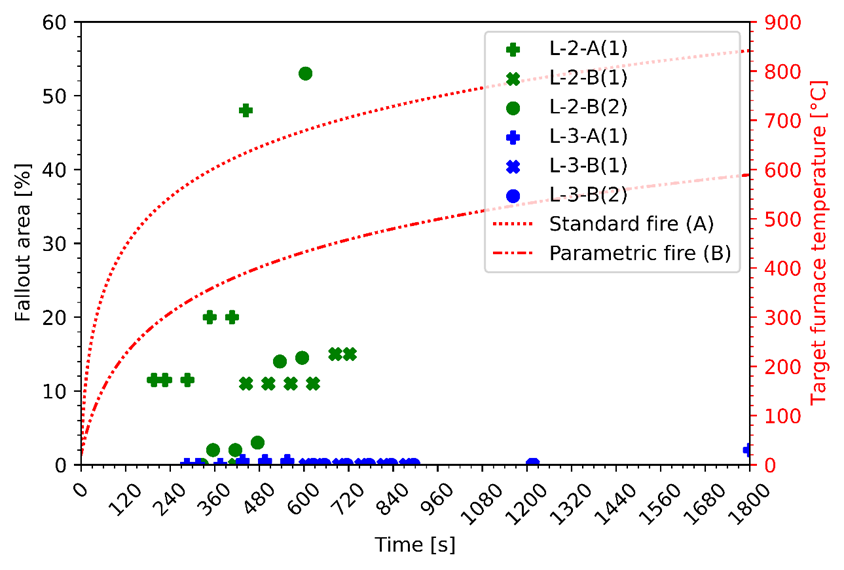

One thing is the cracking time, but the fallout area is ultimately the ventilation opening, and therefore, the single parameter related to window breakage that influences the fire development the most. Figure 4 shows the development in fallout area in time as well as the target furnace temperature of the two fire curves. The fallout area is measured as the opening area over the total area of the window minus the frame. In the tests, the inner glass panes generally experienced a higher degree of fallout, but that is not reported here as it has little significance in terms of ventilation.

Figure 4. Temperature-time curves or the two fires (right axis) and the fallout area in percentage of the total window area (minus frame area) at different points in time (left axis) for each test.

The most noticeable result in terms of fallout area is the difference between the double, and the triple layered windows. It is seen that the fallout of the triple layered windows was almost 0 % in all three cases (note that the two small windows did not crack and therefore also did not have any fallout, but they are not shown in the figure). In contrast, the final fallout area of the double layered windows was between 15 % and 53 %. This difference between the two groups could lead to vastly different fire developments in a real fire.

The data suggests that the fire intensity has negligible effect on both the initial and the final fallout area as the two parametric fire tests for the double layered windows show vastly different final fallout areas with the standard fire being in between. It is also worth noting that the fallout immediately after cracking is not the final fallout as more glass shards form and fall out of the frame in the time after initial cracking. Initially, the window that ended up with the largest final fallout area had the smallest initial fallout, so initial fallout does not seem to indicate anything about the fallout development. Therefore, only focusing on the cracking time and a set fallout area will not accurately describe the ventilation opening.

Conclusions & future studies

Overall, our experiment shows that the double and triple layered windows result in significantly different ventilation conditions independent of the fire exposure. However, in terms of the mechanisms for cracking times, the two types of windows behave similarly. Additionally, our results show a significant impact of the window size on the fire performance with the small windows ultimately being able to survive the fire without cracking of the outmost pane.

The next steps in our research will be to try to make predictions of the cracking and fallout with simulations in Fire Dynamics Simulator (FDS) to see how well the studied phenomena can be replicated with this fire engineering tool. Additionally, we have planned another series of tests focusing more on the effects of different parameters such as low-emissivity coatings and over-pressure in the fire room. All the publications and activities of the research project are made accessible via our project webpage: https://orbit.dtu.dk/en/projects/low-energy-buildings-and-fire-safety/

References

[1] H. Bengtsson, A. A. A. Awadallah, I. Pope, L. Giuliani, and L. S. Sørensen, “Experimental study of the post-flashover fire performance of multi-pane low-energy windows,” Glass Structures & Engineering, vol. 10, no. 3, p. 20, Sep. 2025, doi: 10.1007/s40940-025-00305-3.

[2] EN 1991-1-2, Eurocode 1 - Actions on structures - Part 1-2: Actions on structures exposed to fire. European Committee for Standardization, 2024.

[3] H. W. Emmons, “The Needed Fire Science,” in Fire Safety Science 1, C. E. Grant and P. J. Pagni, Eds., International Association for Fire Safety Science (IAFSS), 1986, pp. 33–53. doi: 10.3801/IAFSS.FSS.1-33.

[4] Y. Wang, “The Breakage Behavior of Different Types of Glazing in a Fire,” in The Proceedings of 11th Asia-Oceania Symposium on Fire Science and Technology, Singapore: Springer Singapore, 2020, pp. 549–560. doi: 10.1007/978-981-32-9139-3_40.

[5] E. Symoens, R. Van Coile, and J. Belis, “Behaviour of Monolithic and Layered Glass Elements Subjected to Elevated Temperatures - State of the Art,” in Challenging Glass 7, J. Belis, F. Bos, and C. Louter, Eds., Ghent University, Sep. 2020. doi: 10.7480/cgc.7.4489.

[6] H. Bengtsson, L. Giuliani, and L. S. Sørensen, “Fire-induced Glass Breakage in Windows: Review of Knowledge and Planning Ahead,” in 8th International Conference on the Applications of Structural Fire Engineering (ASFE), Y. Wang and J. Xiao, Eds., Nanning, China: Guangxi University, Feb. 2024, pp. 21–27.

[7] T. Chu, L. Jiang, G. Zhu, and A. Usmani, “Integrating glass breakage models into CFD simulation to investigate realistic compartment fire behaviour,” Journal of Building Engineering, vol. 82, p. 108314, Apr. 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.jobe.2023.108314.

[8] EN 1363-1, Fire resistance tests – Part 1: General requirements. European Committee for Standardization, 2020.

[9] DS/EN 1991-1-2 DK NA, Nationalt anneks til Eurocode 1: Last på bærende konstruktioner - Del 1-2: Generelle laster - Brandlast. Denmark: Danish Authority of Social Services and Housing, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.bygningsreglementet.dk/nationale-annekser/nationale-annekser/nationale-annekser/

[10] M. Peng, J. Hvidberg, H. Bengtsson, and L. Giuliani, “Fire-Induced Cracking of Modern Window Glazing: An Experimental Study,” in 8th International Conference on the Applications of Structural Fire Engineering (ASFE), Y. Wang and J. Xiao, Eds., Nanning, China: Guangxi University, Feb. 2024, pp. 201–206.

[11] A. A. Joshi and P. J. Pagni, Users’ Guide to BREAK1, The Berkeley Algorithm for Breaking Window Glass in a Compartment Fire, NIST-GCR-91-596. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), 1991.