View the PDF here

Overview of the 2021 Cox’s Bazar Rohingya refugee camp fire in Bangladesh

By: Natalia Flores Quiroz, Stellenbosch University, South Africa

Introduction

On 22 March 2021, a large fire event took place in the Cox’s Bazar refugee camp in Bangladesh. The Cox’s Bazar refugee camp is the largest and most densely populated refugee camp in the world with roughly 980,000 people live there [1]. Due to the fire 15 people died, 560 people were injured, and more than 9,500 homes were affected leaving 45,000 homeless. The fire spread extremely fast, with spread rates much higher than what has been seen in other low-income settlements. With fire events occurring more and more often in refugee camps [2], understanding these incidents becomes critical. This article summarises the findings of a paper published in Fire Technology [3], providing a description of the fire safety in the refugee camps and details about the factors that influenced the fire event outcome. The work was carried out as a collaborative effort between the Migrant Offshore Aid Station (MOAS), the University of Maryland and Stellenbosch University.

Fire safety in the Cox’s Bazar refugee camp

In the last few years there have been many fires in the Cox’s Bazar refugee camp. The International Organization for Migration in Bangladesh has been keeping track of the number of fire incidents that have occurred since 2019. Between April and November 2019, 35 fire incidents were reported, affecting more than 80 shelters. In 2020, during the same period, 47 fire events were reported which affected 3146 people from 700 shelters. The increase in the number of fires indicates that fire safety should be a major concern in these settlements; however, fire safety is far from being a priority due to a myriad of challenges and needs.

As with other low-income settlements, there are many factors that affect fire safety. The use of dangerous sources of energy, such as candles and paraffin stoves, the lack of basic services, narrow roads, the limited number of firefighters, the high density of dwellings, and high fire loads provide the conditions for fires to take place and spread. Focusing on the fire loads, the shelters alone can have fire loads densities as high as 1500 MJ/m2. Figure 1 presents details of the dwellings which are constructed from materials such as bamboo, tarpaulin, ropes (polypropylene, PVC), mortar/concrete and sand.

Figure 1. (a) Camp 8W two weeks before the fire. (b) Standard shelter for fire response showing the bamboo frame and structure clad [4].

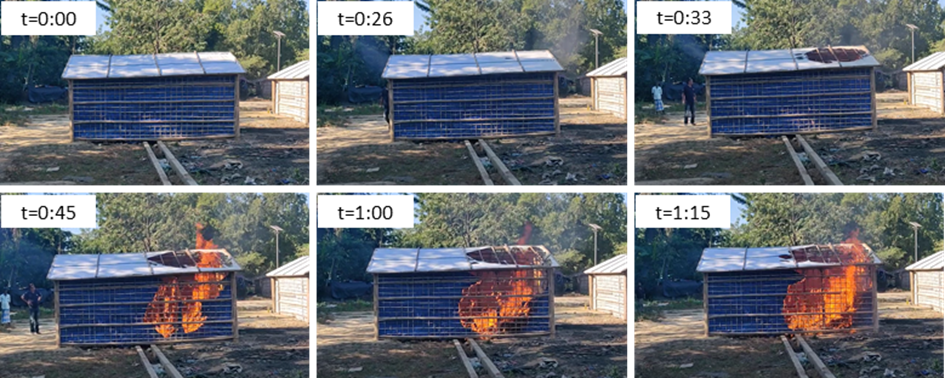

The construction materials used have a direct influence on the fire behaviour of the shelters and on the fire spread to neighboring shelters. Figure 2 presents the fire development at different times in a experimental dwelling on a dwelling. After ignition (at t=0:00) the fire starts to grow and at t=0:26 the tarpaulin on the roof begins to melt. A few seconds later (t=0:33) almost half of the roof has burnt out and small areas of the wall have also been affected. By t=0:45, a large part of the plastic sheet located at the wall has also melted. After this the fire size remains virtually the same. The large openings produced by the fire do not allow the build-up of the smoke layer; hence, the heat is not contained in the dwelling. This is an important difference in comparison to the fire behaviour seen in informal settlement dwellings [5,6], where steel roofs result in a compartment fire rather than a free burning fire.

Figure 2: Screenshots from [7] showing fire development during a tented shelter burning experiment.

The Cox’s Bazar fire incident

On 22 March 2021, between 15h and 22h, a large fire incident took place in the Rohingya refugee camp affecting an area of roughly 0.65 km2. Following the fire, 15 deaths and 560 injuries were reported. More than 9,500 homes were affected leaving 45,000 homeless. Furthermore, many other homes had to be knocked down to create fire breaks. Altogether the incident affected an estimated 47,000 inhabitants. The incident also affected health facilities, nutrition centres, learning centres, child protection centres, and markets.

Fire spread

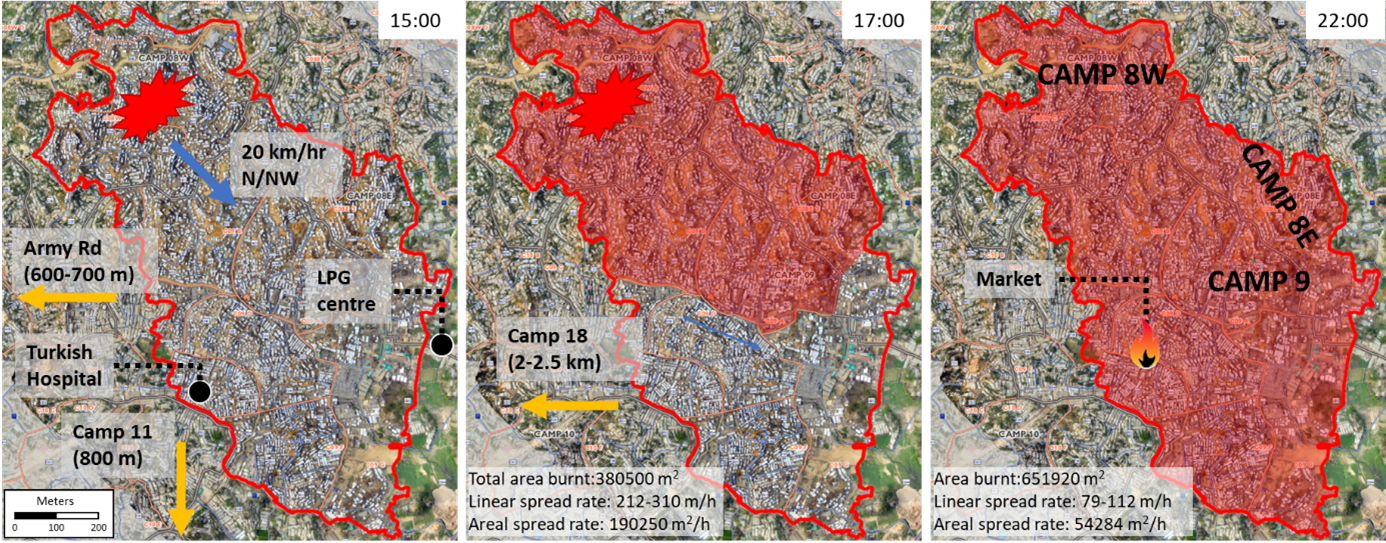

Figure 9 presents the estimated fire spread, it is possible to see the fire scar resembles ones seen in wildland fires. According to eyewitnesses’ statements, there were multiple fires in different parts of the camps, leading them to believe that the fire was intentional. One eyewitness stated, “First, we saw only one fire in block C, then another one, and then one at C18, the fire was started from all sides of our camp”. This could also be due to spot ignitions due to firebrands or hot metal fragments being carried by the wind. It is estimated that in the first two hours the fire affected an area of 380,500 m2, with linear spread rates ranging from 212 to 310 m/h. In the following 5 hours, the fire burnt another 271,420 m2, with linear spread rates ranging from 79 to 112 m/h.

Figure 3: Estimated fire spread of the Cox’s Bazar fire [3].

Firefighters’ operations

Three different organizations provide firefighting services to the refugee camp: the local Bangladeshi fire brigade, the firefighters from an implementing partner organization, and the resident volunteer firefighters. However, there is no Incident Command System that allows for the management of the resources during a fire event. Furthermore, there is no radio network to communicate in the field, which led to the use of WhatsApp for communication. It is interesting to note that the local fire brigade station was designed to only support the local Bangladeshi population of 50,000 people that originally lived in the area, meaning the fire station does not have the capacity and capability to assist the Rohingya community in case of a fire event. Firefighters’ efforts were focused on avoiding the fire to spread to critical areas such as Army Road and the LPG centre in Camp 9, reuniting families and cutting fences.

Residents’ behaviour and evacuation

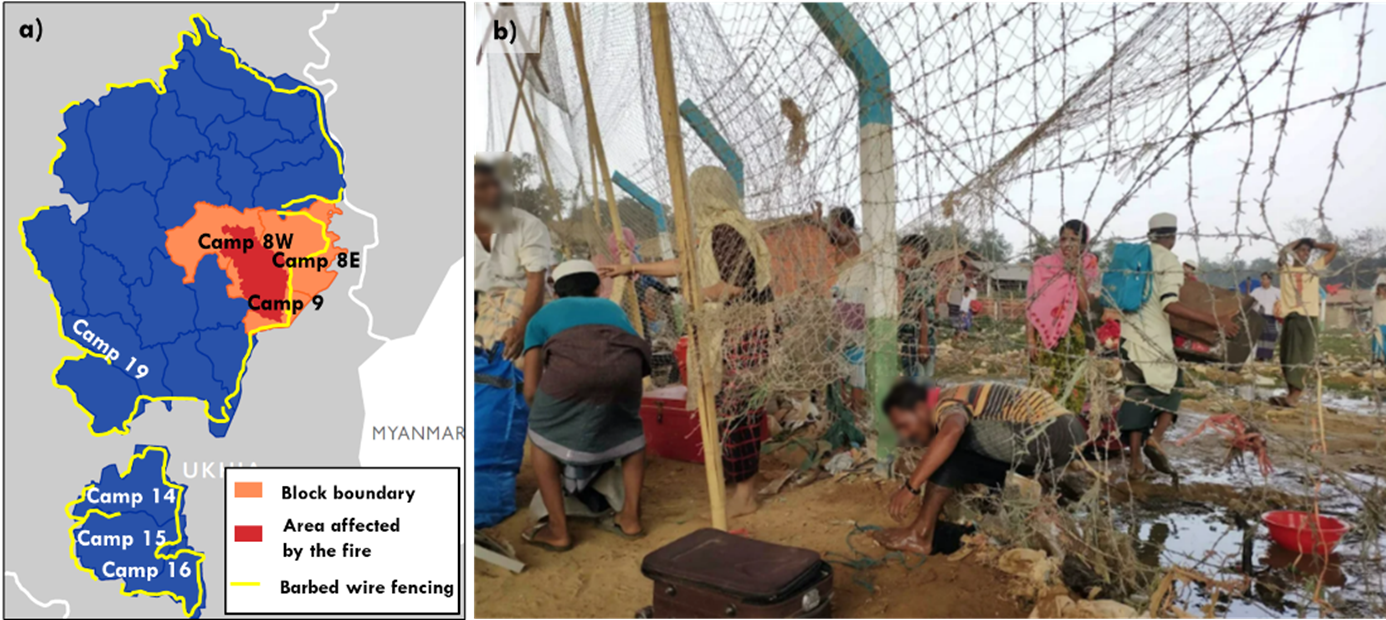

The fact that the fire occurred on a Monday at 15h contributed to the families being separated. Women would typically be at home, men would be in the shops or markets, and the children at the Madrassa or playing outside. The large number of people that got lost or separated could be attributed to this. During the initial stage of the fire some of the residents tried to control the fire, while others went to look for their family and/or save their belongings. The fast fire spread, the dense smoke, the narrow roads, the lack of evacuation plan, evacuation components such as stairs and bridges getting burnt, and the barbed wire fences, among other factors, all impacted the evacuation process. People moved from Camp 9 and surrounded areas towards Camps 14, 15, 16, 19 and 22. Figure 10(a) depicts the location of some of these camps in relation to the area affected by the fire (Camp 22 is located below Camp 16). During the evacuation injuries were reported, and people were lost. Residents and international organizations [8–11] indicated that the wired fence was responsible for many of the casualties, although this hasn’t been confirmed. Very early on the army was cutting the fences to allow people to evacuate. A detail of the location of the fences is shown in Figure 10(a), it can be seen that fire came very close to the fence in the Southwest part of the burn scar.

Figure 10(b) shows a man trying to evacuate through one of the fences.

The evacuation challenges seen in this fire could considered similar to the ones seen in wildland urban interface evacuations face. Some of them are influenced by the lack of accurate information on where to evacuate, insufficient exit routes, delayed evacuations as residents felt the fire would not spread to their homes, and the constant changing of the fire conditions which made it difficult for the recognition and interpretation of fire cues, which increases the risk of having casualties [12].

Figure 4: (a) Area affected by the fire and fence location. Adapted from [13] (barbed wire fencing, approximated location based on [9]). (b) Man trying to evacuate through the wire fencing [14].

Final remarks

Most of fire fatalities occurred in low- and middle-income countries [15]. For this reason, it is important to understand the fire problem in low-income settlements. This is why it is important to understand the fire dynamics and the impact of fire different refugee camp configurations along with geographical and cultural conditions.

The findings from this type of work can be used to (a) plan for future large-scale fire incidents in tented camps by enhancing residents, firefighters’ response and training (b) seek ways of mitigating the impact of fires in these camps, (c) develop and validate fire spread models, (d) guide the development of firefighting equipment that responds specifically to refugee camps, (e) provide input for the development of evacuation models, and (f) to promote general fire awareness in such communities. All of these will assist with the understanding of these incidents in a holistic way, enhancing the response and management of refugee camps fire incidents. However, further research is required before significant developments can be made in a number of these areas.

References

[1] The UN Refugee Agency, Rohingya Refugee Crisis Explained, (2021). https://www.unrefugees.org/news/rohingya-refugee-crisis-explained/ (accessed July 20, 2021).

[2] Y. Kazerooni, A. Gyedu, G. Burnham, B. Nwomeh, A. Charles, B. Mishra, S.S. Kuah, A.L. Kushner, B.T. Stewart, Fires in refugee and displaced persons settlements: The current situation and opportunities to improve fire prevention and control, Burns. 42 (2016) 1036–1046. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2015.11.008.

[3] N. Flores Quiroz, R. Walls, P. Chamberlain, G. Tan, J. Milke, Incident Report and Analysis of the 2021 Cox’s Bazar Rohingya Refugee Camp Fire in Bangladesh, Fire Technol. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10694-023-01406-7.

[4] Shelter/NFI Sector, Standard 10’x15’ shelter for fire response in camps 8E, 8W, 9 Rohingya humanitarian crisis, (2021).

[5] R. Walls, G. Olivier, R. Eksteen, Informal settlement fires in South Africa: Fire engineering overview and full-scale tests on “shacks,” Fire Saf J. 91 (2017) 997–1006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.firesaf.2017.03.061.

[6] A. Cicione, L. Gibson, C. Wade, M. Spearpoint, R. Walls, D. Rush, Towards the development of a probabilistic approach to informal settlement fire spread using ignition modelling and spatial metrics, Fire. 3 (2020) 1–26. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire3040067.

[7] D. Graham, Shamlapur - 2021-11-24 - Shelter 2 (Non FR), (2021). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xeho7THOWM0 (accessed December 7, 2021).

[8] S. Neuman, Hundreds missing in aftermath of fire at Rohingya refugee camp, (2021). https://www.npr.org/2021/03/23/980393127/hundreds-missing-in-aftermath-of-fire-at-rohingya-refugee-camp (accessed December 3, 2021).

[9] Fortify Rights, Bangladesh: Remove Fencing, Support Fire-Affected Refugees, (2021). https://www.fortifyrights.org/bgd-inv-2021-05-05/ (accessed November 25, 2021).

[10] L. Mas, Rohingya refugees fight to remove deadly barbed wire at Bangladesh camps, (2021). https://observers.france24.com/en/asia-pacific/20210503-bangladesh-cox-bazar-rohingya-refugies-camps-barbeles-clotures-remove-the-fence (accessed December 3, 2021).

[11] France24, Bangladesh defends use of fences after Rohingya camp blaze, (2021). https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20210324-bangladesh-defends-use-of-fences-after-rohingya-camp-blaze (accessed December 3, 2021).

[12] E. Kuligowski, Evacuation decision-making and behavior in wildfires: Past research, current challenges and a future research agenda, Fire Saf J. 120 (2021) 103129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.firesaf.2020.103129.

[13] The UN Migration Agency, Fire Incident in Rohingya camps, 2021.

[14] Human Rights Watch, Bangladesh: Refugee Camp Fencing Cost Lives in Blaze Security - Measures Should Be Proportionate, Not Cause Harm, (2021). https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/03/25/bangladesh-refugee-camp-fencing-cost-lives-blaze (accessed March 2, 2022).

[15] N. Flores Quiroz, R. Walls, A. Cicione, Developing a framework for fire investigations in informal settlements, Fire Saf J. 120 (2021) 103046. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.firesaf.2020.103046.